“There are decades when nothing happens,” Vladimir Lenin once observed, “and there are weeks when decades happen.”

Changes that seem impossible for so long can, in an instant, unfold in a way that later seems inevitable. Sixty years ago today, just such a revolution took place in the long stalemate over civil rights.

For President John F. Kennedy, the civil rights movement had long been little more than a nuisance. Elected on a razor-thin margin with a coalition that awkwardly linked together white segregationists in the South and African Americans in the North, the young Democrat believed the issue would tear his party and his presidency apart. Accordingly, he proceeded with an abundance of caution, convinced that any action on the issue would be politically fatal.

As a candidate, Kennedy promised to end all racial discrimination in federal housing projects “with the stroke of a pen” once he took office. But when years passed with no action, black voters mailed him thousands of bottles of ink and ballpoint pens in a mocking “Ink for Jack” campaign. In some ways, the president even made the situation worse. Following the custom of letting senators steer judicial appointments for their states, Kennedy installed dozens of Jim Crow judges across the South, entrenching segregationists in the federal courts just when the civil rights movement needed them most.

Activists were bewildered by his actions. “I’m convinced he has the understanding and the political skill,” Martin Luther King Jr. sighed, “but so far I’m afraid the moral passion is missing.”

In the late spring months of 1963, Kennedy finally discovered that moral passion. Throughout the month of May, networks and newspapers had brought home the brutalities of segregation as civil rights protests in Birmingham reached their climax. Images of lawmen battering black children with high-pressure hoses and attacking them with German shepherds had made the president “sick,” he confessed to aides. The president’s attitude was starting to shift, but his actions remained unchanged.

Campaign Trails is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

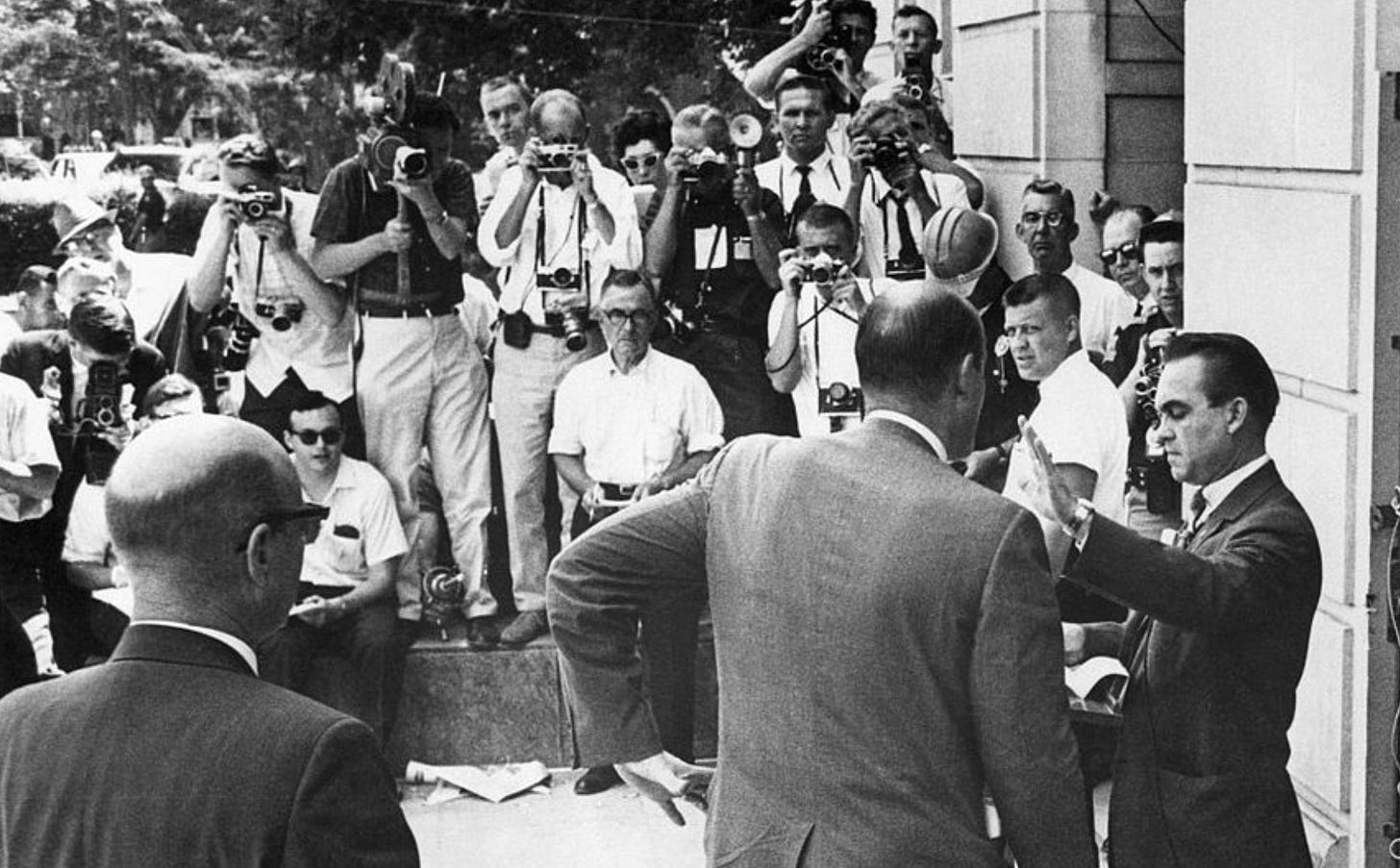

Just weeks later in June, segregationist Governor George Wallace staged his infamous “stand in the schoolhouse door” at the University of Alabama. On June 11, 1963, Wallace went to Tuscaloosa to block the admission of two black students to the all-white campus, but intervention from the Justice Department forced him to back down, with a crowd of cameramen recording his retreat. While the nation worried that Alabama would see an ugly repeat of the deadly white riot that rocked Ole Miss the summer before, in truth, the showdown between Wallace and Deputy Attorney General Nick Katzenbach was all for show -- as the reverse angle of that iconic photograph makes clear.

Once again, the nation was treated to an ugly image of segregationists—sneering, defiant, and somewhat ridiculous. This time, though, Americans could see their federal government fighting back. By the end of the hot afternoon, all sides were satisfied -- George Wallace had secured his defiant photo op, while Vivian Malone and James Hood had successfully registered as new students and officially integrated the university.

Emboldened by the scene, the president impulsively decided to unveil his plan for new civil rights legislation that very night with an address from the Oval Office. “We are confronted primarily with a moral issue,” Kennedy declared with newfound confidence. “It is as old as the Scriptures and as clear as the American Constitution.” The time for patience had passed, he insisted, and the course for action was clear. The civil rights bill he proposed would confront a range of discriminatory measures and empower the federal government to act with authority for its black citizens. “I think we owe them, and we owe ourselves,” he noted, “a better country.”

For those on the front lines of the struggle, the president’s address was a godsend. “I have just listened to your speech to the nation,” Martin Luther King Jr. wrote hastily from his home in Atlanta. “It was one of the most eloquent profound and unequiv[oc]al pleas for Justice and the Freedom of all men ever made by any President.” NAACP President Roy Wilkins agreed, calling the address a “clear, resolute exposition of basic Americanism.”

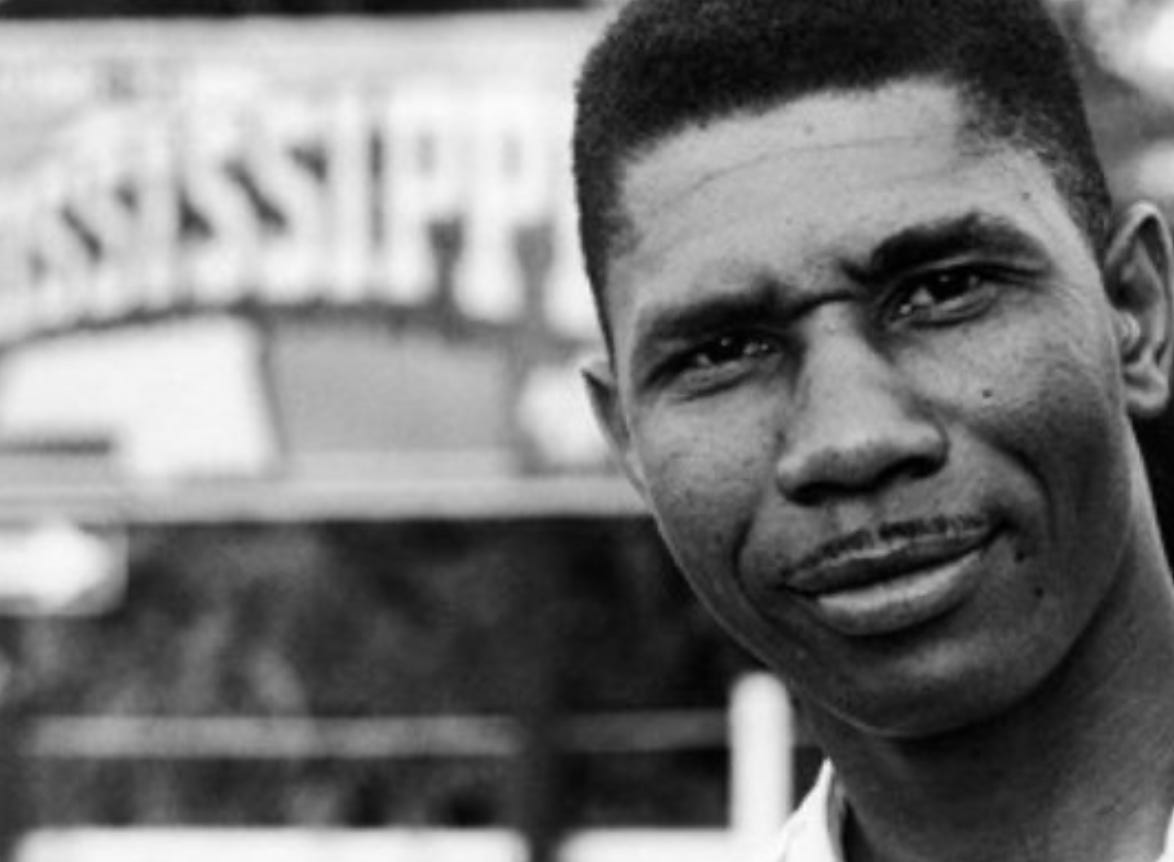

In Jackson, Mississippi, the family of the NAACP’s state field secretary, Medgar Evers, pictured above, waited up late to see what he thought of the speech. Around midnight, the children heard his Oldsmobile pull into the driveway. Evers got out, picked up a stack of sweatshirts stenciled “Jim Crow Must Go,” and turned to enter his home. Across the street, hidden among the honeysuckle vines, a white fertilizer salesman named Byron de la Beckwith squinted through the scope of a 30.06 Winchester rifle, squeezed the trigger, and ripped a bullet through the activist’s back. At the crack of the gun, the kids inside threw themselves to the floor, precisely as their father, a veteran of the Normandy landing, had trained them. When no more shots came, they hurried outside to find him face down and bloodied in their driveway. Within an hour, Evers was dead.

In the early hours of June 12, 1963, Medgar Evers passed away. After the civil rights breakthroughs of the day before, in Tuscaloosa and Washington DC, and across the country, too, his assassination proved a powerful reminder of just how much further the nation still had to go.

For a century after the Emancipation Proclamation, the campaign for racial equality had been repeatedly stalled and stymied, as white supremacists tightened their hold on the South and white politicians at the national level stood by unable or unwilling to help. But now in June 1963, the prospects for progress suddenly — amazingly — changed for the better. The path to the Civil Rights Act would be long and hard, and the list of casualties that long preceded the martyrdom of Medgar Evers would sadly continue to grow along the way. But a crucial change had come.

As we look around our nation today, with our assumptions about what’s possible and what’s impossible in our political system, it’s worth remembering that major changes can often seem inconceivable, right up to the point when they’re not.