There’s been a lot of discussion recently about whether or not Donald Trump should be disqualified from running for office again due to the Fourteenth Amendment’s bar against anyone who previously swore an oath to defend the Constitution but later “engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the [Constitution], or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof.”

In recent weeks, a number of prominent legal scholars — including ones with thoroughly conservative credentials, such as these two Federalist Society law professors or former federal judge J. Michael Luttig — have made a strong case for his disqualification on Fourteenth Amendment grounds.

Now, I Am Not A Lawyer™ so I’ll leave the debate about the merits of this approach to others. But, look, I am a historian, so I can state that the assertion that this approach is, as Rep. Peter Meijer tweeted last night, “a ‘novel legal theory’” is factually wrong.

Despite the claims that disqualification is far-fetched and impractical, it has actually happened before. In the aftermath of the Civil War, six different officials were barred from holding office due to their participation in that rebellion against the Constitution.

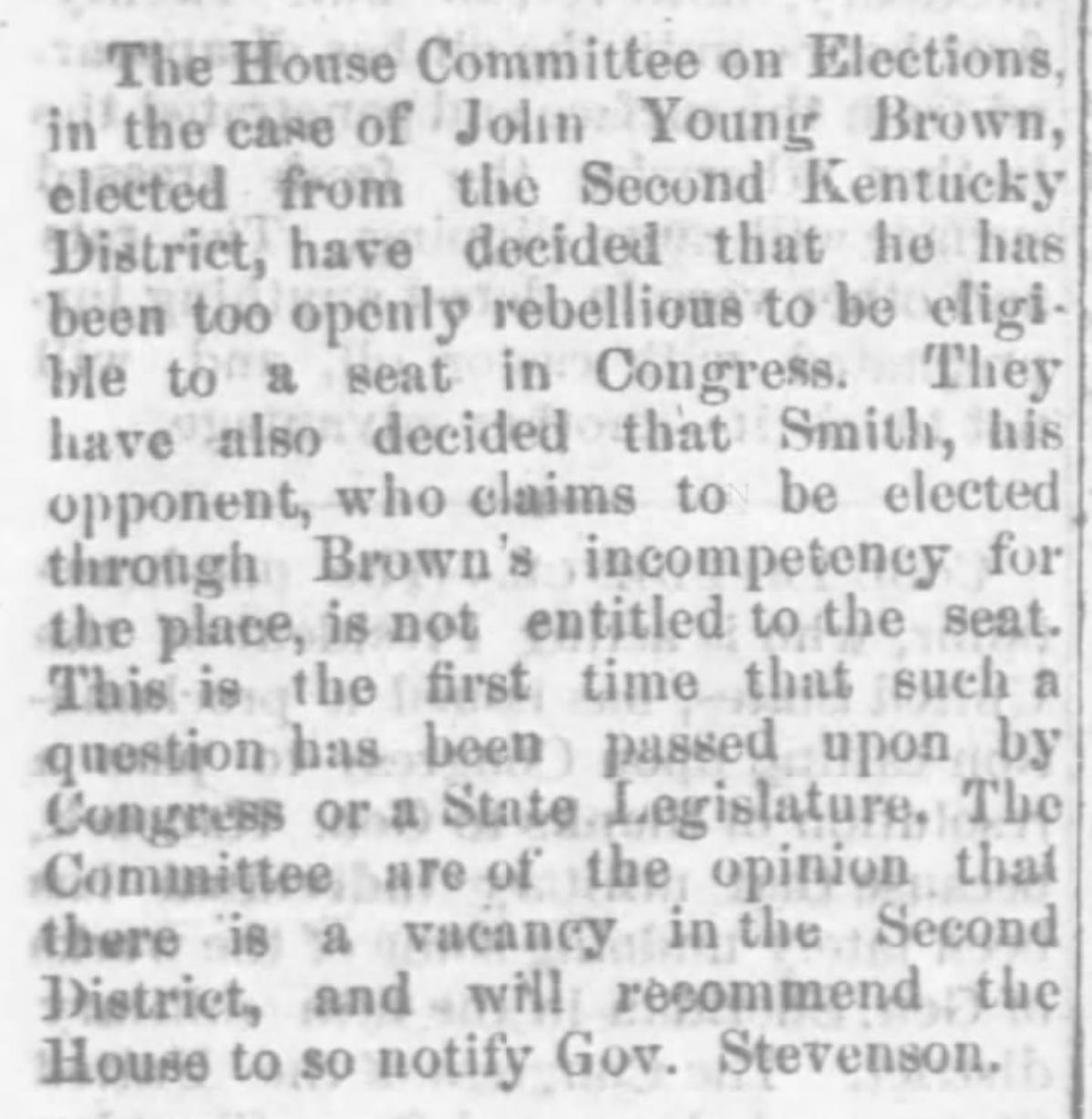

In 1868, former Representative John Young Brown of Kentucky was blocked from retaking his seat in the House of Representatives for his role in the Civil War. Brown later secured a pardon and served two terms in the House and a stint as governor of Kentucky. But for a time there, yes, he was disqualified from office:

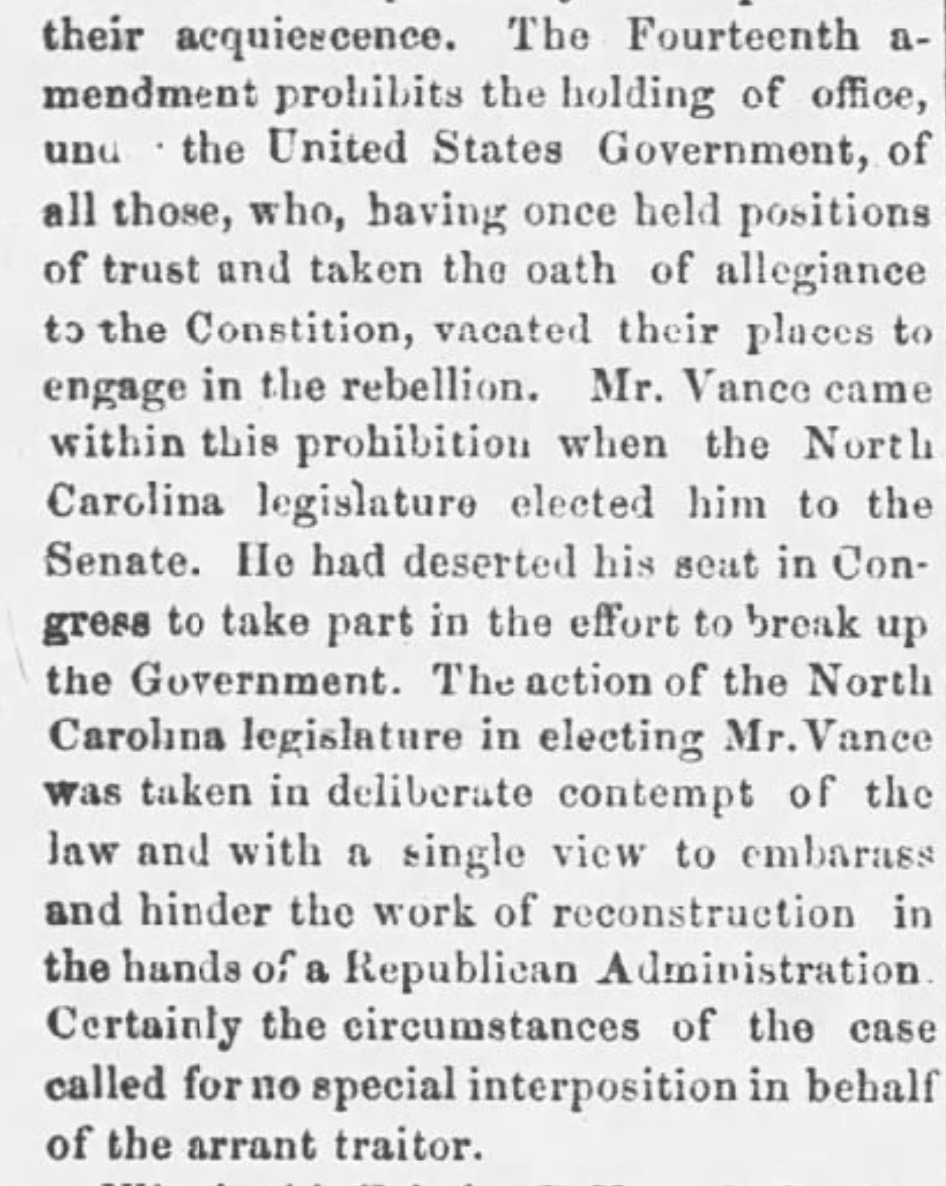

Likewise, in 1870, the North Carolina state legislature had picked Zebulon Vance to fill a vacancy in the U.S. Senate, but Republicans in the Senate refused to seat him for two straight years, on Fourteenth Amendment grounds. Like Brown, Vance was later pardoned then allowed in. But again, until that pardon, he was deemed disqualified.

So, far from being a “novel legal theory,” 14th Amendment disqualification was employed by both the House and Senate within years of its passage. (For a party that claims to respect “original intent,” Republicans seem intent on missing the fact that the people who wrote, passed and ratified the Fourteenth Amendment quickly used it this way.)

But was it just meant for the Civil War? For people who took part in protracted armed rebellion against the U.S. government?

No.

In 1918, former one-term Representative Victor Berger, a Socialist from Milwaukee, was likewise deemed disqualified from making a return to federal office. Berger had written editorials opposing America’s entry into the First World War, which was enough to earn him a conviction for “disloyal acts” under the Espionage Act. His conviction came after his election but before his swearing-in, when the House voted almost unanimously to bar him, 309-1.

In all of these cases I’ve mentioned, the decision to disqualify an official was made by the legislative body itself — the House or the Senate — but the Fourteenth Amendment doesn’t actually specify that they’re the only ones who can make this determination.

Just last year, a District Court judge ruled that a New Mexico official who took part in the January 6th insurrection was likewise disqualified from holding office under the terms of the Fourteenth Amendment. "He took an oath to support the Constitution of the United States,” the judge ruled, but then he “engaged in that insurrection after taking his oath.”

We can (and will!) debate whether or not the Fourteenth Amendment should be used to disqualify Trump.

But the claim that it’s never been used before is simply not true.

Each decent citizen of a state who puts trump on the ballot has standing to sue the Secretary of State and attempt to have him barred. This should happen the instant the ballot is out.

Much as I loathe Trump, he is the choice of millions of voters. To use technical legal maneuvers to deprive them of their right to vote for their choice under these circumstances just seems undemocratic to me. And it is quite likely to lead to real violence and bloodshed, even possibly civil war.