You might have seen this story about an incarcerated teacher in an Illinois prison who was fired from his teaching position there for having the audacity to claim that the literacy tests used in the Jim Crow South were part of a racist scheme to suppress the black vote.

According to the lawsuit, McNeal taught the class at Centralia for almost a year before he was fired. On March 1, 2023, a student in the class asked McNeal about the Jim Crow laws. McNeal then described the use of poll taxes and literacy tests as a means to suppress the Black vote.

Nathan Tucker, the prison counselor supervising the class, interrupted McNeal and instructed him to present literacy tests “as having a legitimate nondiscriminatory purpose of ensuring that voters ‘knew what they were voting for’,” according to the complaint. Tucker did not respond to a request for comment.

As most of you are probably aware, this is complete and utter nonsense. But it’s probably worse than you think.

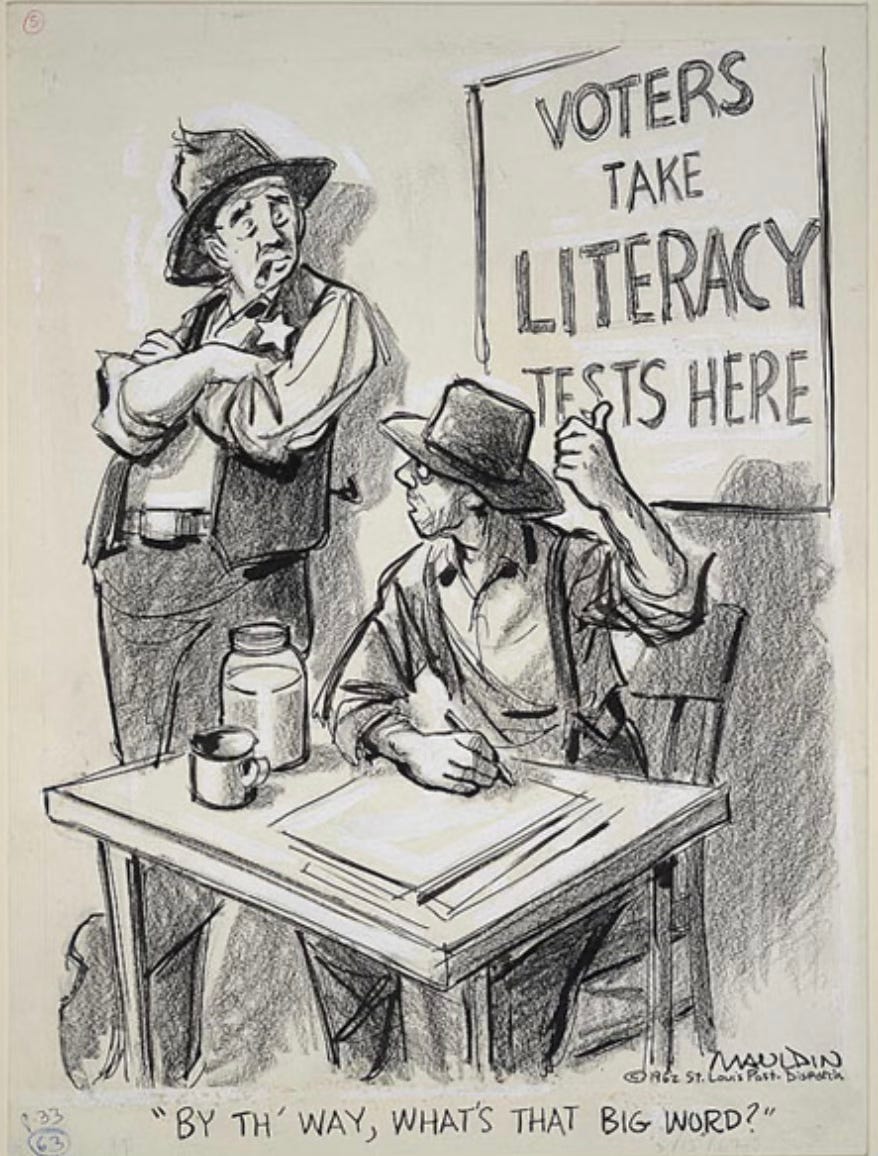

First and foremost, it’s ironic that Tucker’s rationale rehashes the exact same arguments made by southern segregationists at the time. They insisted that literacy tests would simply ensure that the electorate was capable of performing the duties of citizenship, that basic literacy was essential if voters were going to read the candidates’ positions and make an informed choice in the election.

But in practice, of course, the “literacy test” usually strayed far from that professed purpose. The tests varied wildly from state to state, but the one thing they had in common was that they were structured in a way that would let voting registrars at the county level have a plausible reason to reject any and all African Americans as “illiterate.”

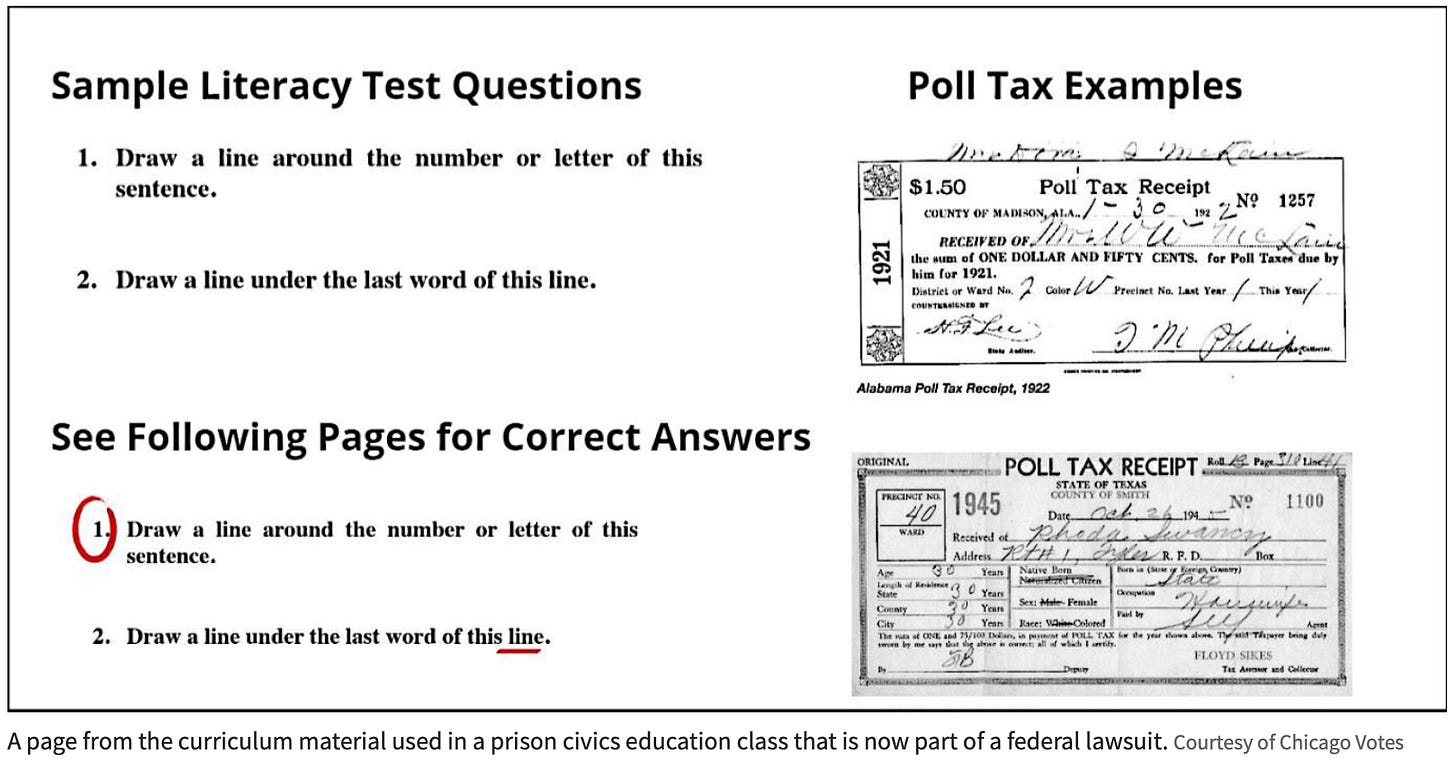

Here’s the example he used in class:

It’s not clear which state the example came from, but it seems to follow the pattern of an infamous and particularly egregious “literacy test” used in the state of Louisiana.

As you can see, these questions have absolutely nothing to do with assessing the basic reading ability of the prospective voter and everything to do with ensuring that a registrar could find a way to mark them wrong. (The example in the original article has the “correct” answers spelled out in red, but registrars could and often did claim that even those answers were wrong. They never had to give a reason; they could just say the applicant failed.)

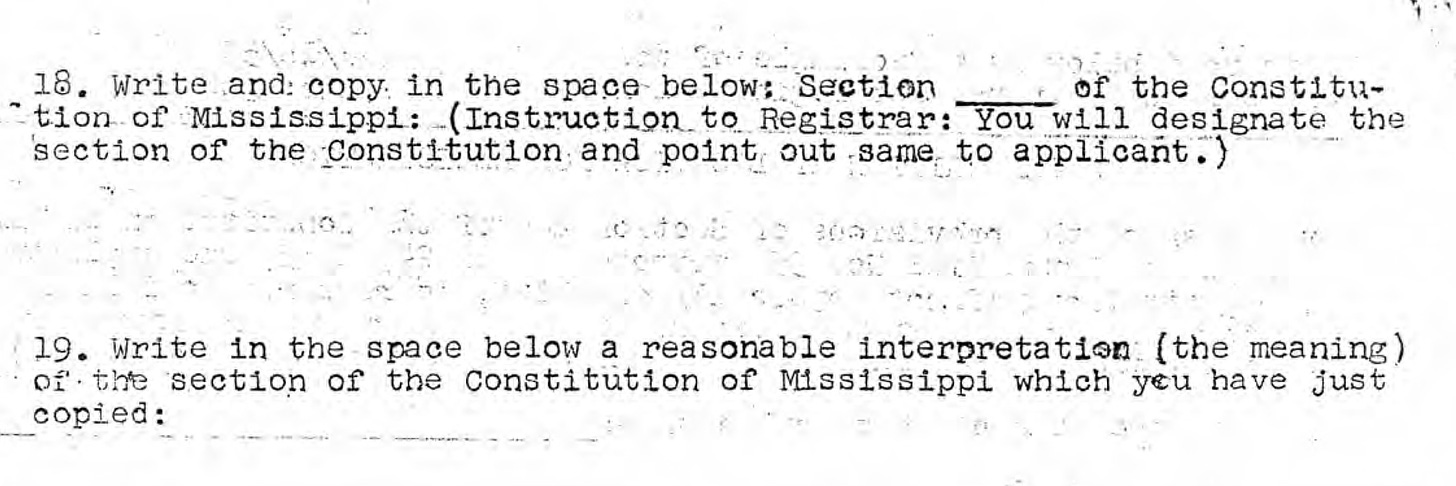

More often, though, the literacy test seemed to have something to do with actual literacy. In Mississippi, for instance, the state adopted a requirement for a two-part “reading and understanding test” as their main way to block blacks from registering.

In theory, it worked like this: an applicant would be given a section of the state constitution, would write it down on the form, and would offer their own explanation of what it meant. That’s a higher standard for “literacy” than simply being able to read, but – in theory – if it were applied evenly, it would be fine.

But of course, it wasn’t applied evenly.

First of all, many registrars had a practice of reading the section out loud to black applicants and then flunking them if they failed to get every word down verbatim. With white applicants, however, they usually handed them the card so they could transcribe it more directly.

Second, though state officials insisted that registrars would randomly assign sections of the state constitution to applicants, that didn’t happen in reality.

The close review of the records by the Civil Rights Division usually showed a pattern in which the shortest, simplest sections were given to whites and the longest, most convoluted sections were given to blacks. In Lauderdale County, for instance, the Division lawyers found that large numbers of whites were given the shortest section of the state constitution, one that read, in its entirety: “There shall be no imprisonment for debt.” Whites had to copy that short seven-word passage, but African Americans were usually given sections that were hundreds of words long.

Third, the interpretation aspect was also handled incredibly unevenly.

The bar was set incredibly low for white applicants, to the point that failure was almost impossible. That question about imprisonment for debt? As Division lawyer Frank Schwelb recalled, “The records disclosed that two whites were accepted although they wrote no constitutional interpretation at all, many wrote unresponsive or nonsensical interpretations, and three passed although they wrote answers which were standard interpretations of a section different from the one assigned to them, but plain gibberish as responses to their ‘test.’” Twelve whites, he marveled, had been registered even though they wrote “No one can be placed in prison for death.”

African-Americans, meanwhile, were given much more complex questions that dealt with incredibly intricate matters of government, getting deep into the weeds on matters of tax rates, bonds, rules that governed the operation and membership of the state legislature or various executive offices, even intricate matters concerning corporations and railroads. In one lawsuit against a registrar in Hattiesburg, the segregationist judge Harold Cox said he wanted to hear what a black applicant had said about a particularly tricky section on taxation because “the Supreme Court of Mississippi has had some trouble with this section.”

As a result of these unequal practices – in assigning sections and assessing the answers – large numbers of illiterate whites were deemed “literate” while significant numbers of well-educated African Americans, including large numbers who had earned not just college degrees from southern schools but even advanced degrees from prestigious northern universities like NYU, Cornell and Columbia were declared “illiterate.”

As the federal government and the federal courts soon agreed, these kinds of “literacy tests” might have appeared to be non-discriminatory on paper, but in practice they were regularly deployed as a racist tool of voter suppression.

Not incidentally, this sort of discrepancy – between what a law says and what a law does, with different racial groups experiencing the supposedly race-neutral law in decidedly different ways – is exactly the kind of thing that is examined and exposed by Critical Race Theory. Which, of course, is why they’re trying to ban it.

But hey now — you better not say that’s racist, either.

My parents (who were from Vermont and NYC, white, born in the early 1920s, and college educated) moved to Northern Virginia in 1961. To register to vote they had to take a test that was given in a white woman's home. They were not able to answer most of the questions but were deemed to have passed the test. Yes, they knew exactly what would have happened if they had not been white.