With Donald Trump set to be arraigned on federal charges this afternoon, we’ve heard a great deal of commentary about what this moment means in the course of American history.

As I noted previously here, the argument advanced by Trump’s defenders — that it’s “illegal and unprecedented” for a former president to face federal indictments — is incredibly weak. It’s absolutely not “illegal” and the only reason we haven’t been here before is that Ford pardoned Nixon before indictments against him could come down. (Once more slowly: the entire reason for the pardon, as Ford noted explicitly, was that “Nixon has become liable to possible indictment and trial for offenses against the United States.”)

While Trump’s partisans have been pushing this historical angle, the mainstream media has been advancing another one. The New York Times argued that Trump’s indictment represents a new crossroads for the Republican Party as it would force them to choose between defending Trump and “deferring to a system of law and order that has been central to the party’s identity for a half century.”

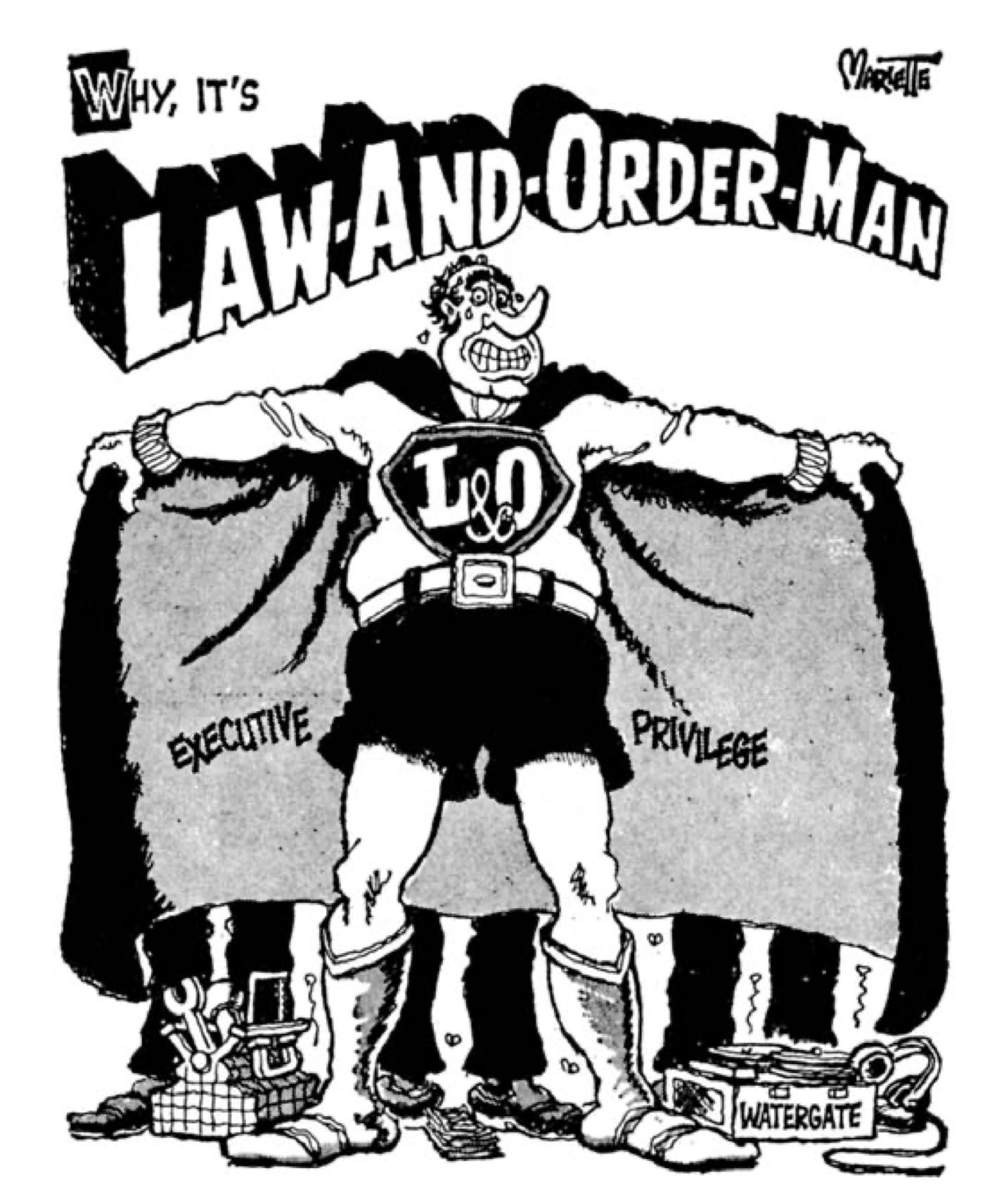

As many noted, though, such a framing missed the huge chasm between the rhetoric of the Republicans and the reality of their actions. Nixon and his VP Spiro Agnew pioneered the party’s campaigns on “law and order,” but both men committed a number of crimes and neither one finished out their second term. Reagan’s team talked about “law and order” while breaking the law in Iran Contra. George HW Bush made “law and order” a central theme of his campaign and then pardoned a lot of the lawbreakers from that same scandal. Etc etc.

This all points to one of the lasting observations about conservatives’ conception of “law and order” from Frank Wilhoit: “Conservatism consists of exactly one proposition, to wit: There must be in-groups whom the law protects but does not bind, alongside out-groups whom the law binds but does not protect.”

Many people assume that “Wilhoit’s Law” comes from the political scientist Francis Wilhoit, but it was actually a blog commenter by the same name. But it’s understandable why people assume the political scientist coined the term, as that Wilhoit’s work was, in an odd coincidence, squarely grounded in the political history that gave rise to the term — the campaigns of racial conservatives to defend the segregationist status quo.

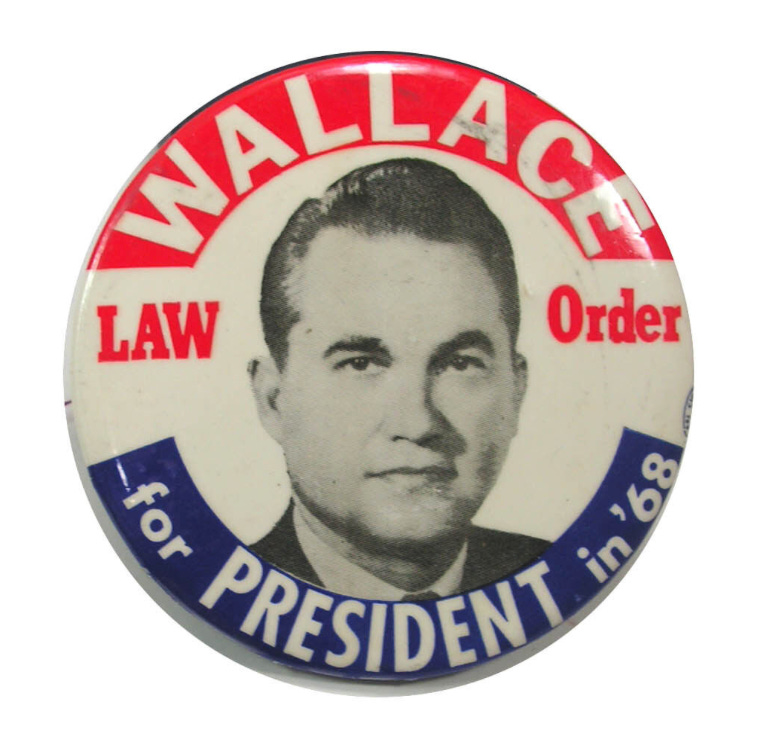

George Wallace, who ran as a Democrat in 1964 and 1972 and made his biggest impression as an independent candidate in 1968, bears responsibility both for popularizing the term “law and order” and cementing its not-so-subtle message that it was directed solely at those on the left who were agitating for social change — first, the proponents of civil rights who engaged in disruptive protests against local laws, and then the anti-war activists of the late 1960s who sought to resist the draft laws.

Nixon and Agnew appropriated that language and those attacks as part of the larger “southern strategy” I’ve detailed here, using it as a way to win over Wallace voters and expand the Republican Party.

That has been the version of “law and order” that’s been “central to the party’s identity for a half century” — a version that is trained solely at their targets on the left and wholly willing to ignore violations on the right. And just as Republicans were able to shout about “law and order” for others as they pressed ahead with Watergate, Iran-Contra and more they’ll continue to shout about it now even as they insist the law never be applied to Trump. It’s entirely consistent.

Your writings and comments always remind me of why I majored in history back in the "dark ages" of 1970-1974!

(My last undergrad class ended on the day Richard Nixon took off in that helicopter to California. 😁)