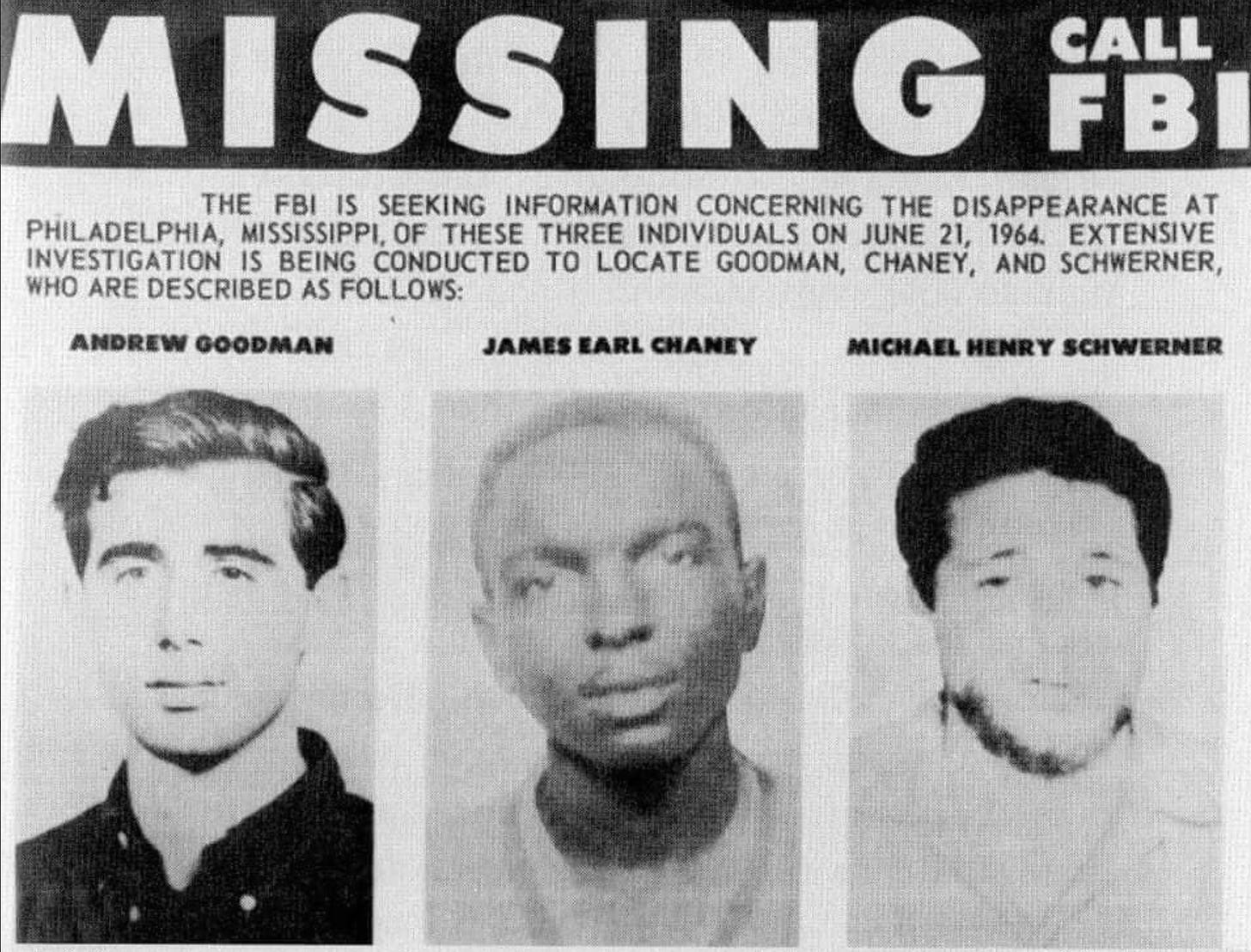

Today marks the anniversary of one of the most brutal chapters in the civil rights movement — the murders of Mickey Schwerner, James Chaney and Andrew Goodman.

The three men were all involved in the Mississippi Freedom Summer, an aggressive campaign by activists to register eligible black voters in Mississippi in hopes of finally making their political power manifest. African Americans made up a majority of Mississippi residents in 1964, and yet thanks to decades of discrimination and racial violence, only made up 6.7% of the state’s voters.

The activists working for the Freedom Summer sought to change all that, operating under the auspices of an umbrella civil rights group called the Congress of Federated Organizations (COFO).

Their activism, of course, did not go unchallenged. White supremacists formed a new version of the KKK styled “the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in Mississippi” in February of that year.

In early June, Imperial Wizard Sam Bowers gathered together hundreds of these new Klansmen, telling them that they were an army forged to fight what he called “the nigger-communist invasion of Mississippi.” The COFO effort to register Americans to vote, he warned, was actually “the enemy's final push for victory. . . which may well determine the fate of Christian civilization for centuries to come.”

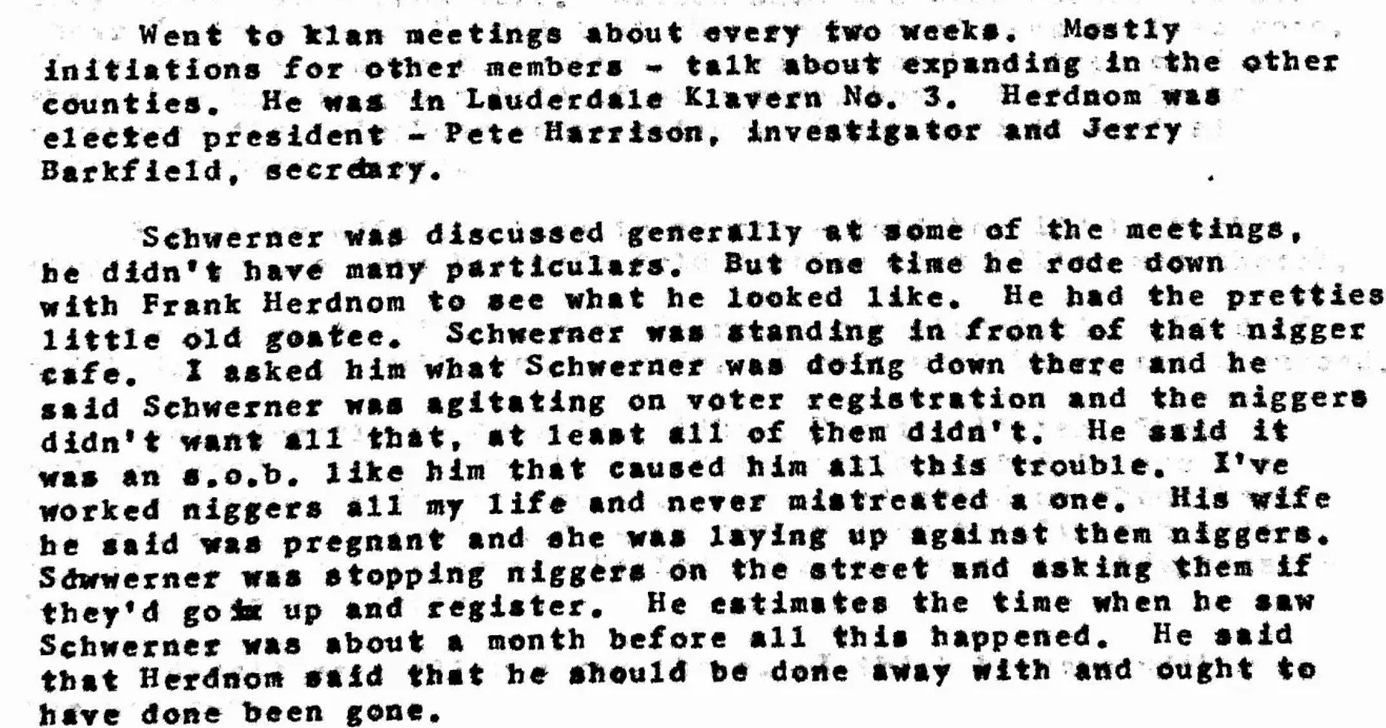

As the Klan sized up their enemy, they took special notice of Mickey Schwerner. A 24-year-old former social worker from New York, Schwerner had been in Mississippi for about six months. Working as a field representative in Meridian for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), he’d led a boycott against a store that depended heavily on black customers but had never had a black employee. His role there put him directly in the Klan’s crosshairs.

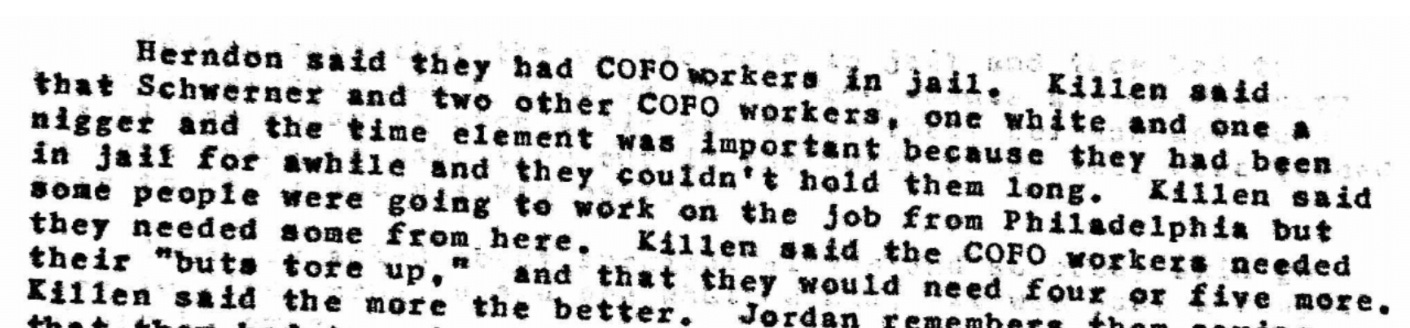

According to FBI informants, Schwerner — who was called “Goatee” or “Jew Boy” — became an obsession for the local Klan chapter in Meridian. Here’s a report from informant Jim Jordan. (All the documents below are from the investigation files in the John Doar Papers at Mudd Manuscript Library.)

Though the Klan singled out Mickey Schwerner, they knew he wasn’t working alone.

James Chaney, a 21-year-old African American and local from Meridian, had come to the local CORE office to help out with the Freedom Summer work and the two soon became close colleagues.

But in addition to local African Americans, Freedom Summer also depended on volunteers from the North — mostly white, middle-class college students — and so Schwerner and Chaney took a trip up to Oxford, Ohio, where a new set was being mobilized. There they met Andrew Goodman, a 20-year-old student at Queens College who was eager to help.

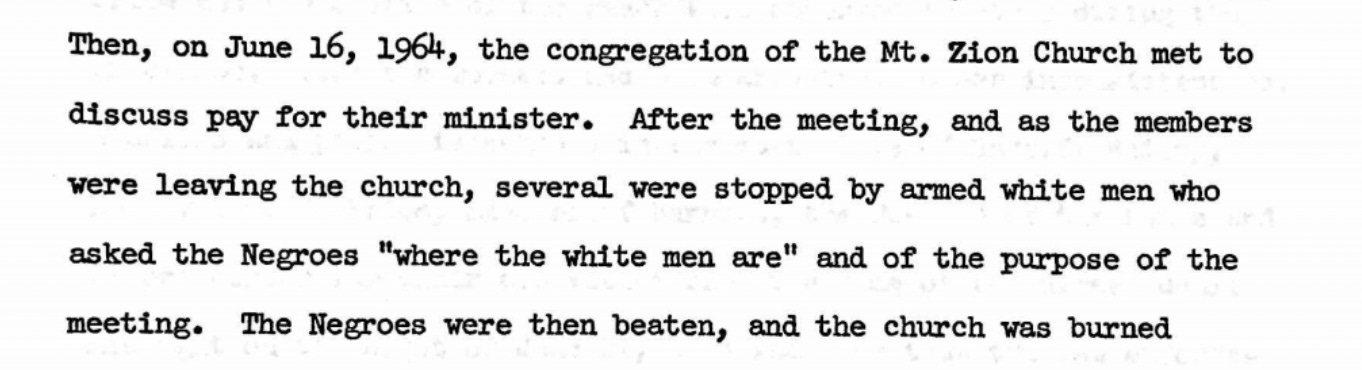

Soon, the three young men got word about a recent incident back in Mississippi.

On the night of June 16, the Mt. Zion Church — which Schwerner and Chaney had previously visited, in hopes of setting up a “freedom school” to educate potential voters — was attacked.

While they were in Ohio, Schwerner learned that the assailants had been asking about the whereabouts of “Jew Boy” and his associates. On June 20, the three men piled into a COFO-owned station wagon and headed directly to Mississippi.

On June 21, they headed from Meridian to Longdale to investigate the church burning. As they made their way back , they were stopped on a traffic pretense by Neshoba County’s Deputy Cecil Price, who was actively working with the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, and detained in the county jail.

When Klan organizer Edgar Ray Killen (below) learned from his fellow Klansman Frank Herndon that “Goatee” had finally been caught, Killen set the plan for their murders in motion:

Deputy Price arrested the three activists on a trumped-up speeding charge in the afternoon, but refused to release them on bail until the Klan could get mobilized. Finally, at about 10:30pm, Price accepted their cash, let them go and told them to get out of Neshoba County as fast as they could.

Two carloads of Klansmen were waiting for them, with Deputy Price bringing up the rear in his patrol car. A high speed chase took them down the highway and onto a back road, where the Klan finally caught them. As they pulled them from their car, they chanted: "Ashes to ashes, dust to dust, if you'd stayed where you belonged, you wouldn't be here with us."

They shot Goodman and Schwerner in the chest. They beat Chaney brutally before shooting him, too. They drove the car across the state and set it on fire.

The bodies of the three activists were buried that night in an earthen dam under construction at a nearby farm.

The Klansmen and their law enforcement allies assumed they would get away with it all. White supremacy in Mississippi seemed impenetrable. The Democratic Party had long defended it, and in 1964, the state Republican Party platform agreed that “segregation of the races is absolutely essential to harmonious racial relations.”

In that climate, the killers felt confident. Sheriff Lawrence Rainey, who knew better, told reporters that he didn’t think they were really missing, but if they were, “they just hid somewhere, trying to get publicity.” Deputy Price spun the same lies, so confident in the cover-up that he concluded his first interview with the FBI by happily clapping the agent on the back and saying “Hell, John, let’s have a drink.”

Here’s Price and Rainey, laughing their way through their eventual arraignment:

Despite the lies of these lawmen, civil rights activists immediately knew something had gone horribly wrong. The three activists had been well trained and when they hadn’t checked in with the local COFO office by late afternoon of the 21st, their colleagues sounded the alarm.

The Justice Department’s John Doar — who had actually been in Oxford, Ohio, to address the activists before they headed down to Mississippi — got a call at 1:30am from SNCC’s Mary King. He convinced the federal government to launch a full-scale investigation. A flurry of activity, involving a special visit from former CIA Chief Allen Dulles, the dedication of the first FBI office in Mississippi by J. Edgar Hoover, and a mass mobilization of FBI agents following leads and Navy sailors working in a search pattern surprised friends and foes of the movement alike.

For some, the sudden surge in federal action was a welcome change but also a worrying reminder of the power of white supremacy. As Schwerner's widow put it, “We all know that this search, with hundreds of sailors [dredging the river], is because Andrew Goodman and my husband are white. If only Chaney was involved,” she said, “nothing would have been done.”

But the government did act, and quickly pierced through the lies and conspiracies at the heart of the murders. An informant’s tip led authorities to the bodies, which offered undeniable proof of a murder and a cover-up, and the FBI and DOJ worked as quickly as they could. But even then they understood what a hold white supremacy had on the region. “In spirit, everyone belonged to the Klan,” lead investigator Joseph Sullivan noted. “It didn't pay to push Neshobans. They weren't afraid.”

But the diligent work of the federal government wore them down. The FBI conducted interviews with nearly a thousand people in its “Mississippi Burning” investigation and produced a report that was 150,000 pages long. John Doar and the attorneys at the Civil Rights Division sifted through their evidence to expose the lies spun by Price, Rainey and others and to expose the terrorist conspiracy.

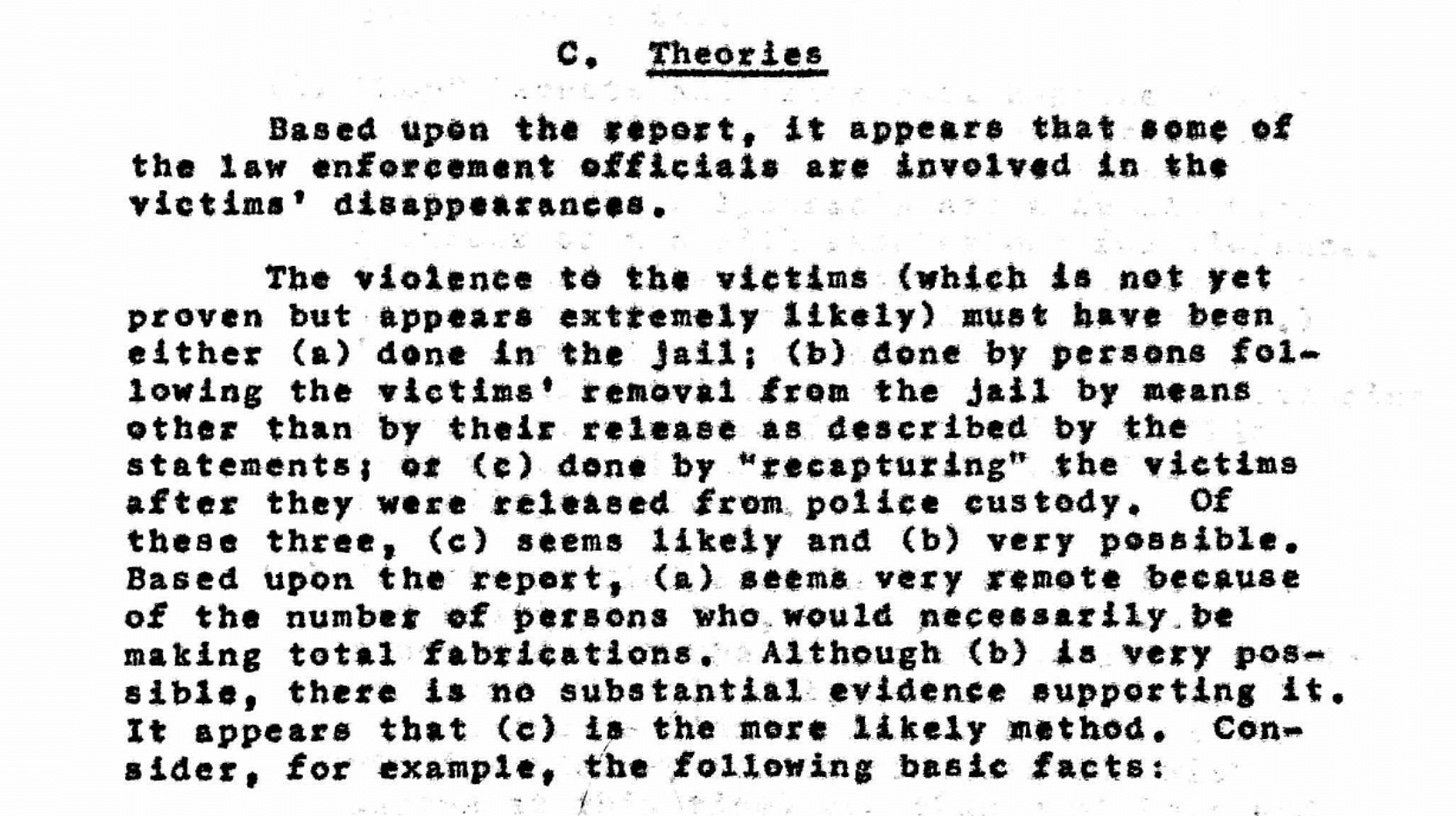

Here’s a memo from a month after the murders, even before the bodies were found:

The road to justice was long, but three and a half years later, John Doar and the DOJ brought the case of US v. Price to a successful conclusion.

I’ll have a lot more to say about this case in my next book (and likely in other posts here at Campaign Trails well before then), but the upshot is that the DOJ secured convictions for seven of eighteen defendants, including Deputy Price and Imperial Wizard Bowers. Sheriff Rainey got off.

Edgar Ray Killen, who played as a part-time preacher in addition to his Klan duties, escaped justice in the initial trial, solely because one woman on the all-white jury said she “could never convict a preacher.”

But the federal trial on charges of a conspiracy to deprive civil rights was just one way to exact justice. After decades of denials and delays, Killen was arraigned on murder charges for his role in the Neshoba killings in early 2005.

And as a result, on June 21, 2005 — forty-one years to the day after the murders — the man who orchestrated the murders of Schwerner, Chaney and Goodman was convicted on three counts of manslaughter. He died in prison thirteen years later.

It’s become a cliché in civil rights histories, but like all clichés it’s a little bit true: the moral arc of the universe is long, but it bends towards justice.

Thanks for the recap. John Doar’s amazing work doesn’t get enough credit with the general public.

I was born in 1955 and grew up in Jackson, MS. My mom was a staunch proponent of Civil Rights. My Engineer father hired a black draftsman in the early 1970s when no one hired black men for white collar jobs.

I want to write here about my experiences growing up - how completely weird it was, looking back on it. No time now - later today or tommorrow. BTW, I googled the names of some of those murderers, and found some good articles, including this from the Oxford American:

https://oxfordamerican.org/magazine/issue-86-fall-2014/no-twang-of-conscience-whatever