On June 25, 1962, the Supreme Court handed down one of its biggest rulings in the “school prayer” case of Engel v. Vitale.

In light of recent proposals calling for a return of school prayer, I thought it might make sense to run through a little of this history. (What follows is pulled from my book One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America.)

Engel v. Vitale began in 1951, when the New York Board of Regents composed a prayer they hoped would be said during the daily flag ceremonies in public schools across the state: “Almighty God, we acknowledge our dependence upon Thee, and we beg Thy blessings upon us, our parents, our teachers, and our Country.”

Some districts immediately adopted the “Regents Prayer,” while others resisted. After a few years of debate, the board in Herricks, Long Island, instituted the prayer in 1958. Complaints rose immediately but when the school board refused to listen, five local parents — a Unitarian, an Ethical Culturalist and three Jews, all who felt out of step in the largely Catholic community — filed a federal lawsuit. The case was styled Engel v. Vitale, after Stephen Engel, the parent whose name came first alphabetically, and William Vitale Jr., the district superintendent

Some of the plaintiffs and their supporters worried the lawsuit would prompt an anti-Semitic backlash. “There were some who thought we shouldn’t do it,” one plaintiff remembered. A rabbi from a nearby town cautioned another plaintiff against taking part, but the man dismissed his warning with an old joke. (Two Jews were brought before a Nazi firing squad. As the soldiers took aim, one started screaming “Down with Hitler!” The other turned and whispered: “Morris, listen. Why make trouble?”)

But they pressed ahead, securing a (Catholic) lawyer from the ACLU to represent them. The lower courts consistently ruled against them, but they kept appealing and wound up with a hearing before the Supreme Court in April 1962.

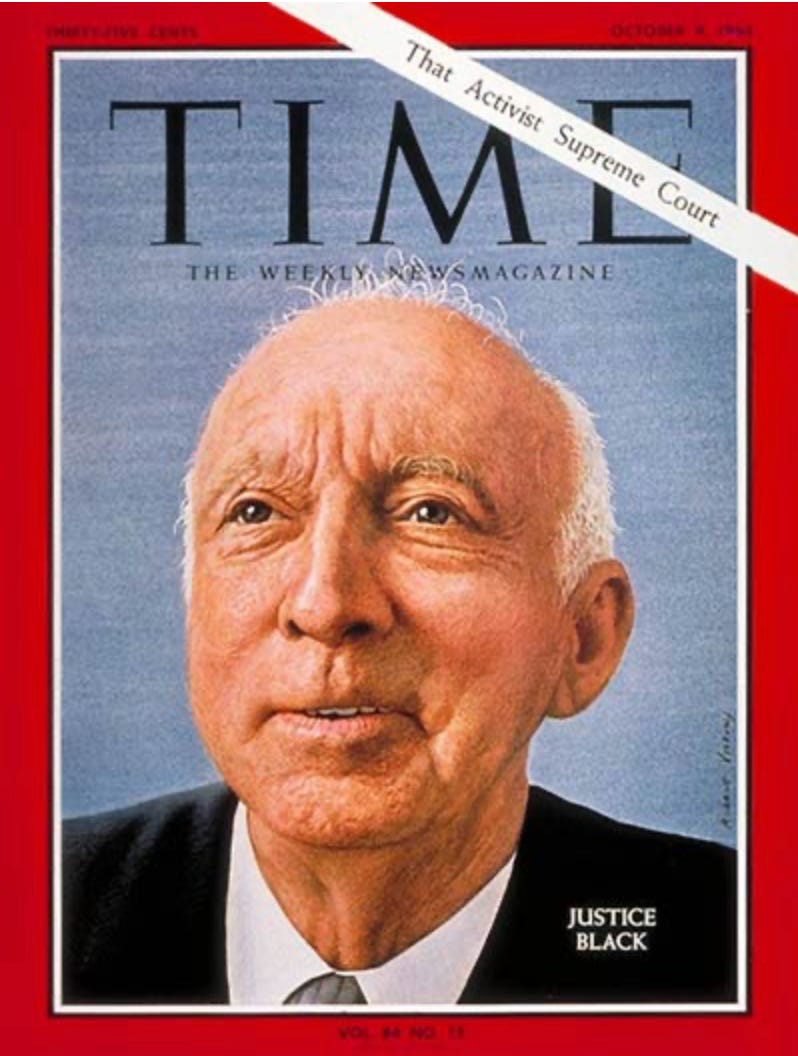

When the oral arguments were over, it was clear to all in the courtroom that a majority was ready to side with the plaintiffs and rule that state-sponsored school prayer was unconstitutional. In their closed-door conference, Justice Hugo Black asked for the case and went to work drafting the opinion.

The Engel case was the culmination of a complicated lifelong relationship Black had with religion.

A native of rural Alabama, Black grew up deep within the Baptist tradition. In 1907, after arriving in Birmingham to practice law, Black became an active member of its First Baptist Church. His pastor, Alfred Dickinson, who had trained at Harvard and the University of Chicago, two bastions of modernist religious thought, was notoriously liberal in his theology. He stood for separation of church and state, welcomed evolutionary biology and textual criticism of the Bible, and dismissed “noisy conversions and ecclesiastical whoopee.” Black, who served as a deacon at First Baptist and taught its adult Sunday School for nearly a quarter century, came to share his pastor’s liberal theology.

Though he harbored doubts about standard Baptist religious doctrine, Black was true to its political traditions, especially its centuries-old call for complete separation of church and state.

Indeed, Hugo Black did much to cement that doctrine in American law. In his landmark opinion in Everson v. Board of Education, a 1947 case involving a New Jersey statute requiring school boards to reimburse transportation costs for parents of parochial schoolchildren, Black argued that neither the states nor the federal government could “enact laws aiding one religion over another, force or influence a person toward or away from a church, belief, or disbelief, punish a person for profession or non-profession, levy a tax to support religious activities or institutions, or participate in the affairs of any religious organization.”

The justice reached back to borrow a metaphor coined in a letter to his fellow Baptists in Danbury, Connecticut, two and a half centuries before. “In the words of Jefferson,” Black wrote, “the clause against establishment of religion by laws was intended to erect ‘a wall of separation between church and state.’”

As he sat down to write the Engel decision fifteen years later, Black was determined to defend that wall of separation.

Religious liberty was essential, he told his wife, because “when one religion gets predominance, they immediately try to suppress the others.” History was littered with evidence of the dangers that inevitably followed when church and state merged. “People had been tortured, their ears lopped off, and sometimes their tongues cut or their eyes gouged out,” Black continued, “all in the name of religion.”

Lower courts had repeatedly made unsubstantiated claims about America’s “religious heritage” to side with the defendants in Engel, but Black was determined to expose their errors with a meticulously researched rebuttal. By the sixth draft, the bulk of his opinion had become a lengthy narrative about the tangled history of church-state relations in the Anglo-American world. “It is a matter of history,” he insisted, “that this very practice of establishing governmentally composed prayers for religious services was one of the reasons which caused many of our early colonists to leave England and seek religious freedom in America.” Based on “bitter personal experience,” Black wrote, the founders crafted the First Amendment to keep the state out of religion and religion out of the state.

On June 25, 1962, the Supreme Court announced its decision in Engel v. Vitale. Inside the courtroom, Black arched forward in his high-backed chair, rested his arms on the bench and began reading the opinion with unconcealed emotion. In the audience, his wife thought his delivery “sounded almost like a sermon.”

After explaining the details of the case, Black paused to collect himself and clutched his papers tightly. There could be “no doubt,” he read, that “the daily invocation of God’s blessings [was] a religious activity” and, as a result, no doubt that New York “adopted a practice wholly inconsistent with the Establishment clause.” Black asserted that the First Amendment embodied the founders’ belief that faith was “too personal, too sacred, too holy to permit its ‘unhallowed perversion’ by a civil magistrate.” (Here, an observer noted, “his voice trembled with emotion as he paused over ‘too personal, too sacred, too holy.’”)

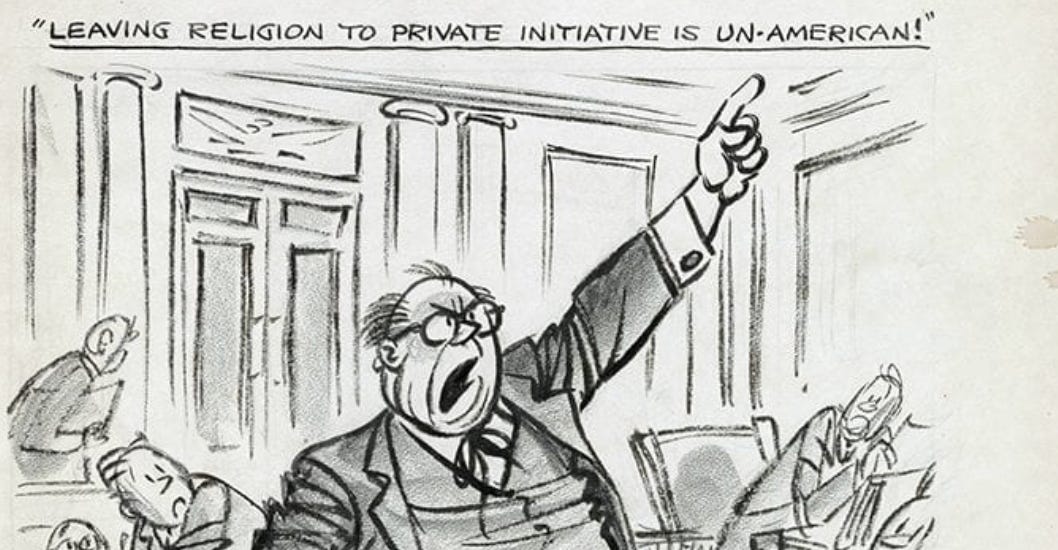

In Black’s view, religion certainly deserved a place of prominence in American life, but the state could not dictate it. “It is no part of the business of government,” he read, “to compose official prayers for any group of the American people to recite as a part of a religious program carried on by the government.” Departing from his text, Black added an impromptu plea. “The prayer of each man from his soul must be his and his alone,” he said. “If there is anything clear in the First Amendment, it is that the right of the people to pray in their own way is not to be controlled by the election returns.”

The court’s majority had gone to great lengths to note that their ruling merely struck down the Regents’ Prayer and, moreover, only did so because of the role that New York state officials played in its composition and implementation. But newspapers lost the nuances. “GOD BANNED FROM THE STATE,” ran a typically hyperbolic headline. Hostile editorials only compounded the problem. The New York Daily News, for instance, lambasted the “atheistic, agnostic, or what-have-you Supreme Court majority,” while the Los Angeles Times complained they made “a burlesque show” of the First Amendment.

The hate mail Black received was staggering in its volume — there’s so much it takes up ten full boxes in the National Archives — and vitriol. A California man fired off a typical litany of fears in rapid order: “Next God will be taken out of the oath of the President; out of the courts; out of the National Anthem, the salute to the flag; off of the coin of the U.S.; out of the Battle Hymn of the Republic; prayer will be taken out of the House and Senate; the national observance of a Day of Thanksgiving to God abandoned,” and finally “Christmas and the Christian Sabbath will be objected and vetoed by our Supreme Court as embarrassing to somebody.” Some imaginations ran even wilder. “How about next time around lets abolish all references to God in official documents,” wrote a woman from Ft. Lauderdale. “Then the third time around lets imprison anyone mentioning God or attending a religious service, & fourth time around – set up the firing squad, & fifth – get your silver platter out & hand us over to you know who.”

For Black, the deluge of criticism was stunning. Reading the angry letters, he said, was a “real education.” He replied to the calmer complaints, often suggesting that his correspondents had been misled about the decision and urging them to read it themselves. He largely ignored the angrier ones, but occasionally felt compelled to respond. “One woman condemned Hugo to Hell,” his wife recalled, “and he wrote an answer telling her a bit sarcastically, I thought, that if she would go to the library (as he was sure she would not have it in her own house) and ask for a book called the Bible, she should turn to the chapter and read where it said ‘Pray in your own closet.’”

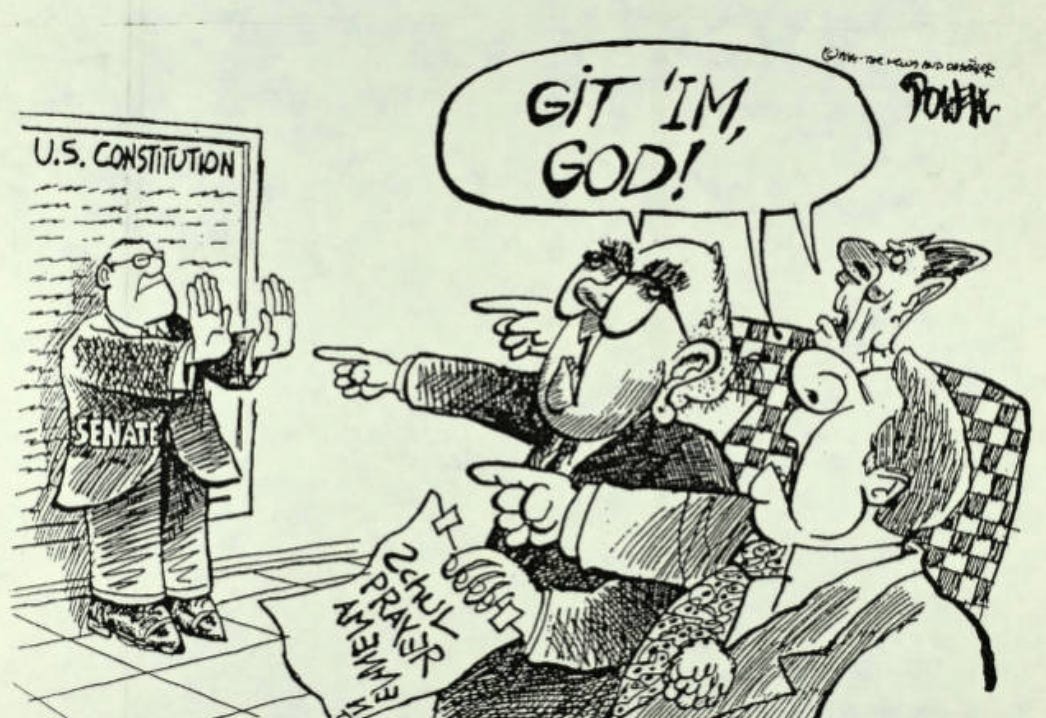

The fury over Engel simmered for a while, picking up more energy when the Supreme Court struck down state-mandated Bible reading in another decision the following year. The country convulsed with the expected outrage from religious conservatives, who pressed for a constitutional amendment allowing school prayer, a push that led to long congressional hearings. (If you’re interested, I cover these at length in the book.)

But ultimately it was religious liberals who won the day. And notably, they did so by stressing that they didn’t want the government writing their prayers for them. They took their religion seriously, they told Congress, so seriously that they didn’t want the government interfering in their realm and imposing a “watered-down, one-size-fits-all faith.” They wanted a wall of separation, these religious leaders insisted, to keep the state out of their religion.

When the storm over the school prayer decision had died down in the mid-1960s, the wall was still standing. There have been perennial challenges for school prayer since then — another big push in the 1980s (the cartoon above), and several small revivals since then — but the wall still stands. And largely because the heirs of Hugo Black stand watch.

"...faith was “too personal, too sacred, too holy to permit its ‘unhallowed perversion’ by a civil magistrate.”" Hmmmmm. Replace "faith" with "bodily autonomy" and we have a strong pro-choice argument. Also a precedent! We know how important precedent is to this Court! 😂

Very interesting article. Thank you.

The school prayer cases combined with Brown v. Board of Ed. had a major effect on the right. I remember school devotionals in public school in Nashville. They abruptly stopped in fourth grade. I’ve read your book One Nation Under God. Another good one is American Apocalypse, which describes Nashville businessman Maxey Jarman as the “renowned evangelical shoe tycoon.” Jarman ran for Governor in the Republican primary. I think he lost to Winfield Dunn.