Following the bizarre bloodletting in the Republican House caucus over the last few weeks, the relatively unknown Rep. Mike Johnson of Louisiana has been elevated to the powerful position of Speaker of the House.

There are a lot of things we don’t know about the man who’s now second in line to the presidency — like whether or not he actually has a bank account or any financial assets as he tries to gut the IRS in his first act — and sadly much of the media is writing gauzy puff pieces where they don’t just go to a diner to ask about him, they literally interview his own mother for insights.

Speaker Johnson has done a lot to keep his personal views hidden, telling reporters asking about his worldview: “Go pick up a Bible.” That’s both a huge humblebrag, implying that all his earthly actions are in accordance with the literal word of God, and a disingenuous dodge that obscures the practical details of his politics.

But Johnson is sticking with that line, as seen in this interview with the Heritage Foundation’s outlet the Daily Signal. And it’s clear from the piece that when it comes to the history of religion and politics in America — both at the founding and in recent decades — Johnson doesn’t really know what he’s talking about. (I hope you were sitting down for that.)

First of all, as Warren Throckmorton has noted here on Substack, Johnson is not surprisingly a devotee of the Religious Right’s favorite pretend historian, David Barton, whose books are so divorced from the actual history that his conservative Christian publisher once had to recall one of them for passing along fake quotes from the Founding Fathers.

In the interview, Johnson does a very familiar routine, cherry-picking a few select quotations from the Founders to imply that they basically wanted a theocratic government, and ignoring the many other quotations from them making clear that these Enlightenment figures absolutely did not want that.

For just one example, Johnson quotes John Adams, who wrote in a letter that “Our Constitution is made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate for government of any other.” He doesn’t note that, in his duties as president, Adams signed the Treaty of Tripoli, which stated quite clearly that “the Government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion.”

The first quote, which he leans on heavily, is the private expression of a single man; the second is an official government position in a binding treaty that was launched by Washington, signed by Adams and ratified by a U.S. Senate whose ranks were half-filled with men who crafted the Constitution. Which one is more indicative of “the Founders”?

And that’s a key point here. When the Religious Right tries to engage us in a game of “quote/counterquote,” we should look past the varied and often contradictory words of the Founding Fathers — who often said contradictory things because they were, you know, arguing with each other — and instead focus on the actual deeds that they accomplished as one.

Don’t listen to a cherry-picked Adams quote about who the Constitution was written for, look at what the Constitution actually says! The only mentions of religion in there are measures that keep religion and government at arm’s length from each other — no religious tests for office holders, no establishment of a national religion, no interference with individuals’ rights to worship or not as they saw fit. That is what the Founders actually wanted.

But Johnson, selling the same snake oil as David Barton, hand waves past all that to imply that the Founders unanimously agreed that Americans had to be religious and that their common government — so carefully constructed to keep religion out of it, and it out of religion — was actually a religious compact in which “there has to be a consensus on virtue and morality,” a consensus which Mike Johnson would surely think embodied his own personal brand of faith.

From that starting point, Johnson argues that his view of religion in politics was “almost universally accepted as truth” throughout American history, and then leaps ahead in the interview to a moment when American political leaders did in fact seem to embrace that as truth:

The United States seems to have lost sight of what actually holds us together, the speaker mused.

“‘E pluribus unum,’ Latin for ‘out of many, one,’ is anchored in the premise that there will be a common consensus that we are one, that there is a truth, and as our nation’s motto articulates very clearly, that we are one nation under God,” Johnson emphasized.

That motto was added in 1962 above the rostrum in the House of Representatives as a rebuke of the Cold War-era Soviet Union, he said, and as a distinction between United States’ beliefs and the Marxist, communist, or socialist premises that God does not exist.

First of all, it’s worth noting that he seems to conflate the original unofficial motto of “E Pluribus Unum,” which was widespread from the founding era, and the more recent official motto of “In God We Trust,” which wasn’t adopted until 1956, to imply that the unity of the original motto was always meant to be a religious one. That’s a wild distortion of the actual history.

So too is that reference to the etching of “In God We Trust” in the House of Representatives. In Speaker Johnson’s version of history, the motto was installed there as a rebuke to the godless commies of the Soviet Union.

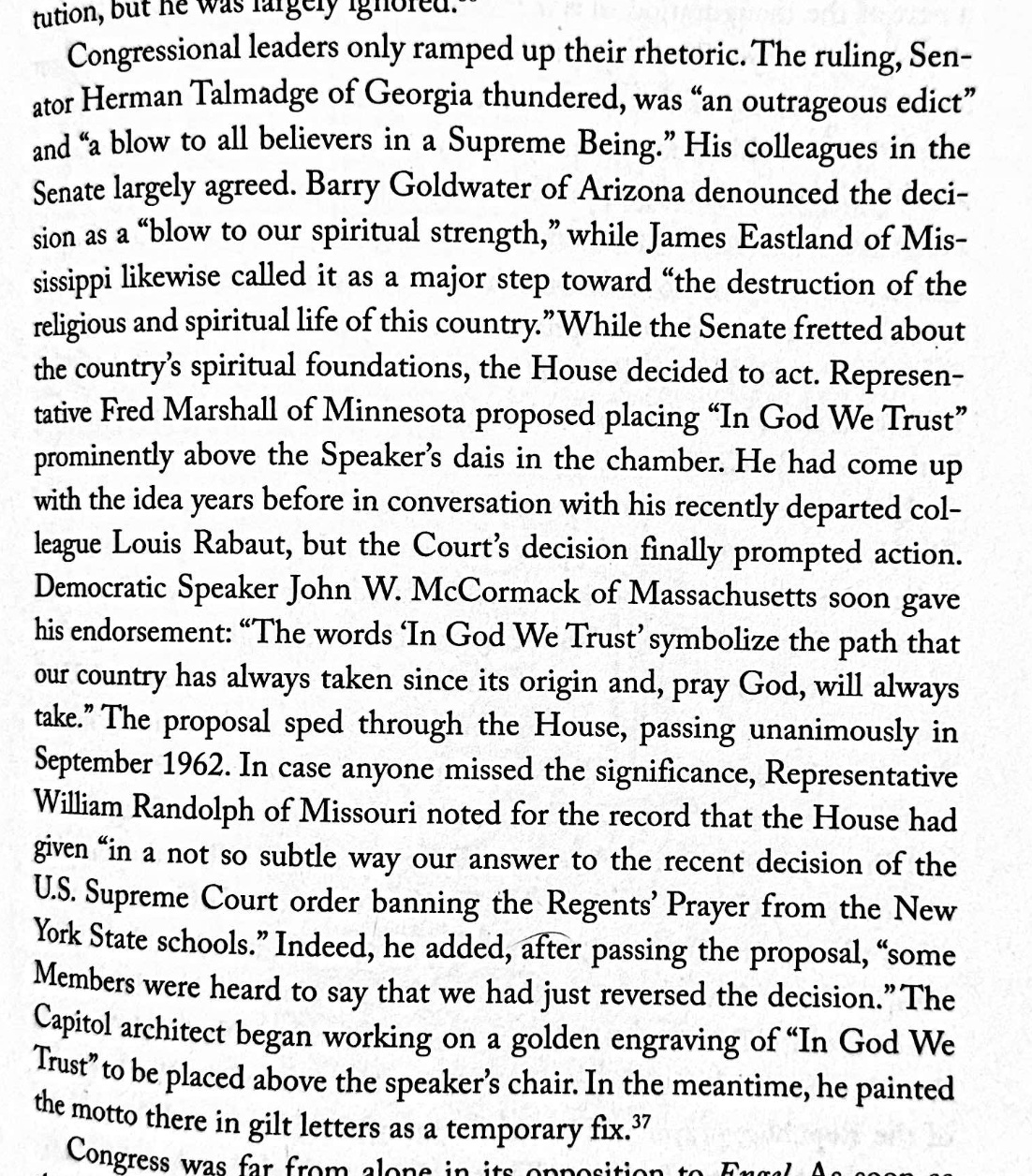

But as I described in detail in One Nation Under God, the reason the motto was added in 1962 was because it was meant as a public rebuke to the godless commies of the Supreme Court, which had just ruled that state-mandated prayers in public school were a violation of the First Amendment. (You know, that thing the Founders agreed on?)

Johnson’s version of history is one in which Cold War Americans, in keeping with an unbroken tradition of blending piety and patriotism, joined together to reaffirm their unanimous support for religion in our government, as a statement against the Soviet Union.

But in the real version of history, Americans had long been deeply divided over the involvement of church and state — even during the Cold War, when yes, religious observance reached unprecedented heights — and the installation of that motto was a shot in the domestic culture war.

Here’s the story in brief from my book:

Now that Mike Johnson is Speaker of the House, wielding the gavel underneath that inscription of “In God We Trust,” it’s important to remember that he’s simply the latest in a long line of partisans who have advanced a badly-distorted history of the American founding in order to justify their own personal political crusades.

As a historian, I can assure you that Mike Johnson isn’t doing what the Founders want. And as a Christian, I’d personally argue he’s not actually doing what the Bible promotes.

Mike Johnson is doing what Mike Johnson wants. And no matter how hard he tries to wrap it in the flag and the cross, his agenda is quite extreme.

I confess (!) I was slightly surprised and I admit a bit disappointed to learn that you are a Christian. I add you to the list of the people I most admire who are religious. One of my best friends is a fairly devout Muslim. But I don’t understand it.

Thank you for this and all that you do.

“The first quote, which he leans on heavily, is the private expression of a single man; the second is an official government position in a binding treaty that was launched by Washington, signed by Adams and ratified by a U.S. Senate whose ranks were half-filled with men who crafted the Constitution. Which one is more indicative of ‘the Founders’?”

Excellent way to differentiate - thank you! Will be sharing this widely.