Today is the anniversary of the signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which means we’re guaranteed to see plenty of social media posts about how A Higher Percentage of Republicans Voted for the Civil Rights Act.™

Consider this post a handy pre-buttal for your convenient use if you encounter this nonsense at Facebook, Twitter, or, God help you, a family barbecue.

First and foremost, we should note how unusual and contorted this kind of claim is.

It’s always a bit messy determining who “deserves credit” for a particular piece of legislation, given that there are invariably hundreds if not thousands of people involved in a long, multipart process. (Schoolhouse Rock, I regret to inform you, vastly simplified the ordeal.)

But, look, if you want to give one party or another credit based on the congressional votes, you count the votes. The actual number matters; a percentage doesn’t tell us much. (When the Social Security Act was passed in 1935, for instance, it won Senate votes from 60 out of 69 Democrats, 16 out of 25 Republicans and 1 out of 1 from the Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party. That last one technically had the highest percentage — a perfect 100%! — but that doesn’t mean we give one man credit for passage.)

The reason some on the right (cough) play the partisan percentage game is that it takes our eyes off the actual numbers. But, again, the numbers matter.

For starters, it’s worth remembering what the numbers in Congress were in 1964. In the House, Democrats had an overwhelming margin (258 Democrats to 158 Republicans); in the Senate, they had nearly a 2-to-1 advantage (64 Democrats to 36 Republicans). As you see, Democrats were the dominant party in both houses.

But, of course, at this moment in its evolution, the Democratic Party was far from united on the matter of civil rights. Southern conservative segregationists had long tied the party to white supremacy, but northern white liberals and African-Americans had for decades been steadily gaining ground.

Because of these dynamics, the congressional battle over the Civil Rights Act was, at heart, an internal fight within the Democratic Party. Liberal Democrats pushed for the bill; conservative Democrats pushed back to stop them.

This dynamic is abundantly clear when we look back at the history of the Civil Rights Act before its passage.

Democrats clearly led the campaign for the civil rights bill. A Democratic president introduced the bill. Democratic leaders and committee chairs shepherded it through both houses of Congress, which Democrats controlled. It passed the House with votes from 153 Democrats (and 136 Republicans) and the Senate with votes from 46 Democrats (and 27 Republicans). Another Democratic president signed it into law with Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders at his side.

But at the same time, Democrats clearly led the resistance against the civil rights bill. Across the South, Democratic Governors like George Wallace denounced the measure and Southern Democrats in Congress worked tirelessly to obstruct its progress at every single turn. When it came time to vote, 91 Democrats (and 35 Republicans) voted against it in the House and 21 Democrats (and 6 Republicans) voted against it in the Senate.

Look at those vote totals. You can see Democrats and Republicans on both sides. Claiming one party was monolithically for or against the act obscures the range of ideological and regional differences inside both party coalitions and reduces political history to a simplistic morality tale. The truth, as always, was more complicated.

Yes, Southern Democrats in the Senate did filibuster the Civil Rights Act. But we should note that the only Southern Republican senator joined the filibuster too, and the filibuster's leader, Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, soon switched to the GOP.

On the flip side, yes, significant numbers of northern Republicans — mostly liberals and moderates, but some key conservatives like Ohio Rep. William McCulloch, ranking member of the House Judiciary Committee — worked with the majority of Democrats to pass the Civil Rights Act, as Democratic leaders recruited them to make up for the Dixiecrat defections.

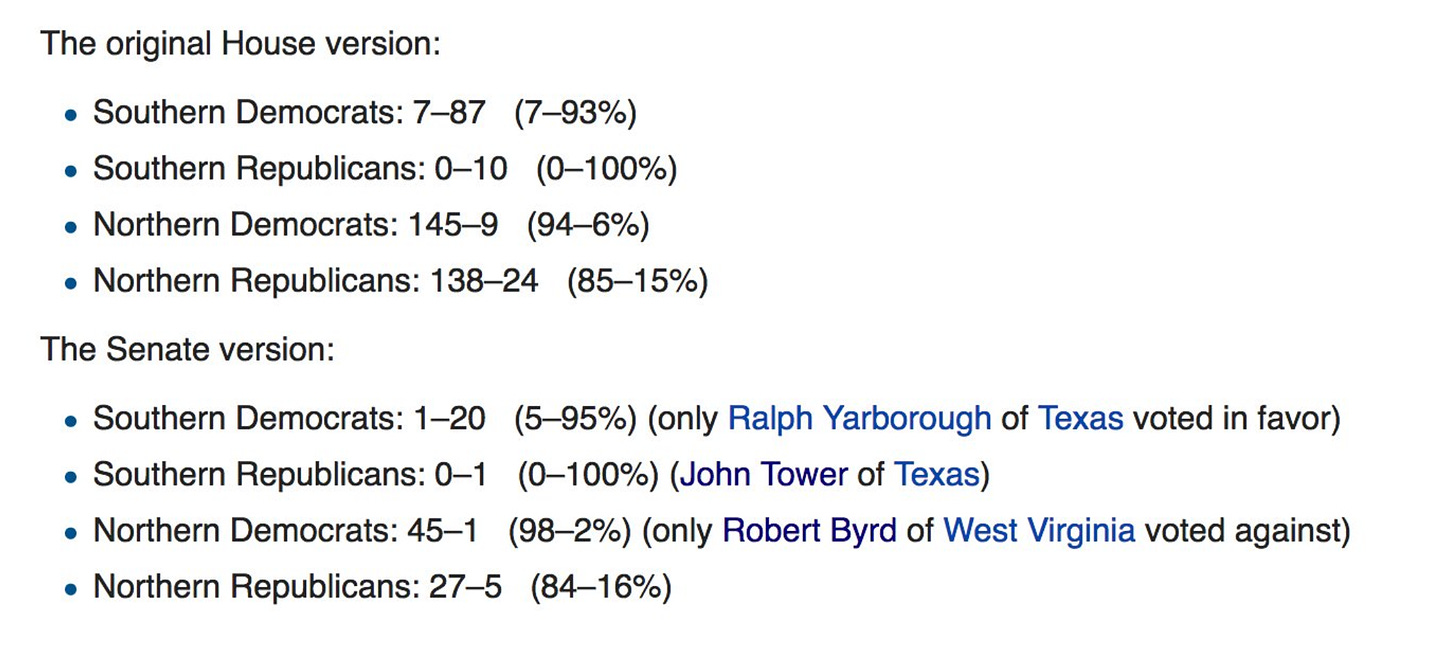

The real distinctions to make here are along lines of region and ideology, not party. Put simply, southern conservatives in both parties resisted it.

Here's the vote broken down by region:

All right, now we can get back to the sleight of hand that lies at the heart of the percentage game.

The conservative pundits who make that argument are essentially trying to use the votes of mostly liberal and moderate Republicans, to claim that not only was the Republican Party “the party of civil rights” in 1964, but also that it still is today.

This is ludicrous. When this all unfolded, conservatives were engaged in civil war with these liberals and moderates, trying to drive them out of the Republican Party.

At the 1964 Republican National Convention — which took place just two weeks after President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law with Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders at his side — the GOP nominated Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater to represent them in that year’s presidential race. Though not personally a bigot, Goldwater believed the federal government had no role to play in civil rights and, accordingly, he had voted against the Civil Rights Act that Johnson signed.

The liberal and moderate voices in the Republican Party, who made common cause with liberal and moderate Democrats in the congressional fight, now found themselves on their own and under attack from the rising ranks of conservatives.

New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, a longtime Republican champion of civil rights, called out the party’s extremists at the convention and was roundly booed:

And the floor fight at the convention was in many ways a literal one.

The handful of black delegates who hoped the GOP was still “the party of Lincoln” were stunned. “They call you ‘nigger,’” a northern black delegate told reporters, wiping tears from his eyes, “push you and step on your feet.” Baseball legend Jackie Robinson, who had long supported the GOP, staggered from the convention hall deeply shaken: “I now believe I know how it felt to be a Jew in Hitler's Germany.”

That same convention adopted a platform that significantly scaled back the party’s previous support for civil rights. You can read them yourself and see the progression — in 1960, Republicans had a lengthy detailed section on civil rights with an aggressive agenda; in 1964, just a few vapid lines; in 1968, not even a mention of “civil rights” at all. (At the state level, the shift could be even more dramatic. In 1964, the Mississippi Republican Party’s platform stated: “We believe in separation of the races in all phases of society.”)

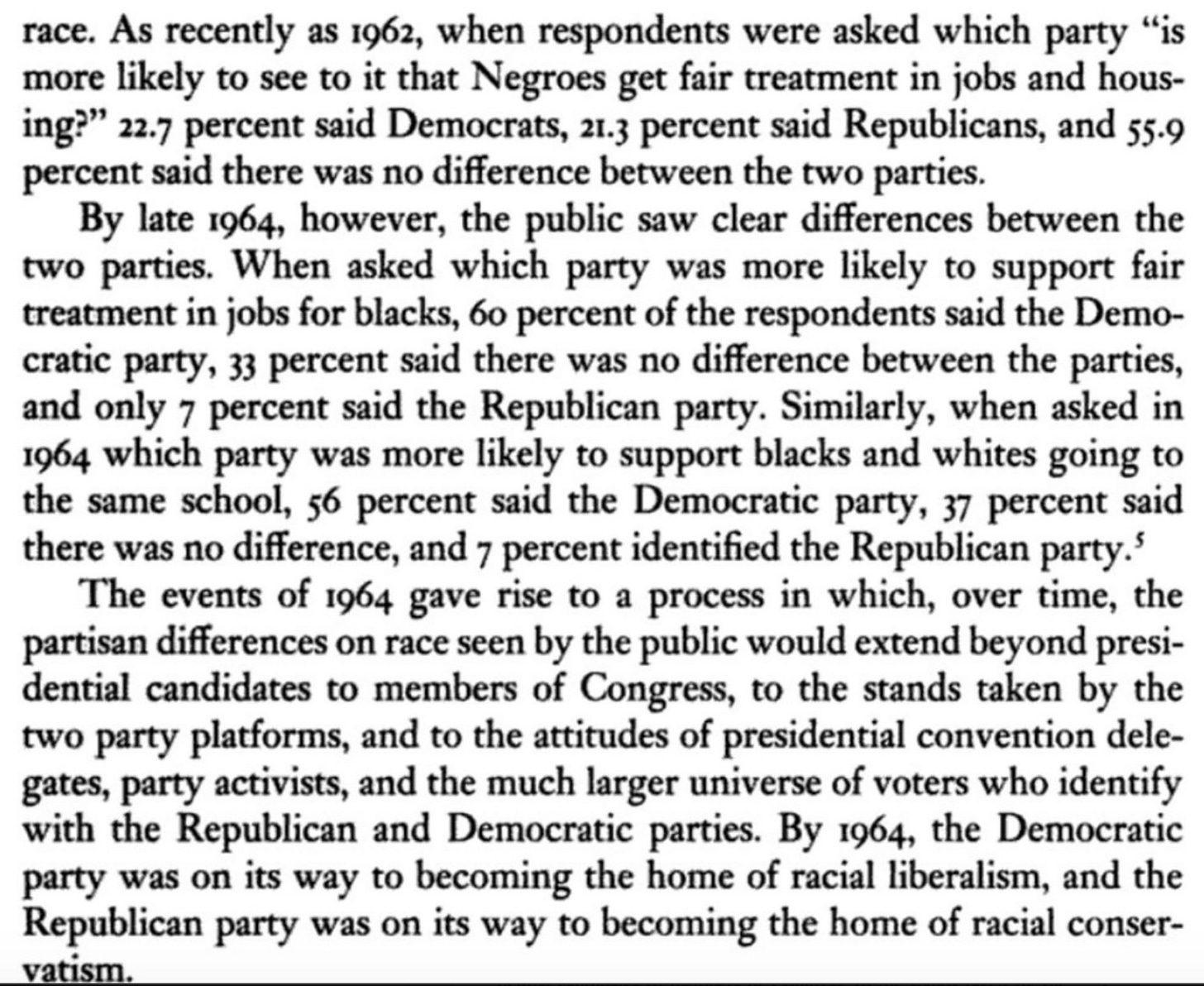

These larger political developments created a clearer narrative for contemporary Americans than the congressional vote on the Civil Rights Act ever did. Thomas and Mary Edsall noted the dramatic shift in polling attitudes on civil rights in this period, showing that in 1964 only 7% of Americans believed that the Republican Party was the better party on civil rights issues.

So, no, the GOP was not “the party of civil rights” in the 1960s. There were, to be sure, moderates like Nelson Rockefeller who stood up for the cause, even ardent conservatives like William McCulloch who provided crucial support as the Civil Rights Act made its way through Congress.

Goldwater Republicans fought them for control of the party and ultimately won, driving out many of those civil rights supporters. (Most dramatically, Senator Thomas Kuchel of California, a prominent liberal Republican who co-managed the bill in the Senate and refused to back Goldwater in 1964, was successfully primaried from the right in 1968.)

In the end, it's bizarre that conservatives who see themselves as the heirs of Goldwaterism now try to reach back to reclaim votes of moderate and liberal Republicans — whom Goldwater conservatives hated at the time — to provide cover for today's GOP.

Sorry. You didn't want them then. You don't get to claim credit for them now.

Kevin, I so appreciate your writing and scholarship. I’m hopeful that your efforts to make known the historical context for today’s events will help prevent us from the doom of repeating history, albeit has begun already.

Also, thank you for moving to Substack, I no longer have to search unsuccessfully through Twitter to find your voice. ( But maybe throw in a little Sarge now and then.)

one of my cousins worked in the senate democratic cloakroom at the time of the vote so my family got word of the ins and outs from within. your narrative of the complexities then, and of the misappropriation by today's alleged conservatives of a glory to which they are not entitled, is a salutary rebuttal to such obfuscators.