Few social movements trace their birth to an event as unexpected and dramatic as the one that gave public life to the cause of gay liberation.

On Friday, June 27, 1969, a group of Manhattan police officers set off to close down the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in the heart of Greenwich Village. Raids of gay bars were common enough occurrences in the 1960s, and the police probably viewed their mission as a routine activity. But this time, as I’m sure you know, the patrons of the Stonewall Inn fought back.

(If you’re looking for a great documentary on it all, I highly recommend PBS’s outstanding Stonewall Uprising which has terrific interviews with the customers as well as the cops.)

There will doubtlessly be a lot of discussion of the uprising today, but one aspect that seems important to stress at this moment — as forces on the right try to create a dividing line between gays and lesbians on one side and transgender people on the other — is that these groups have long shared a common history of exclusion and discrimination. And that was never as clear as it was at Stonewall.

Transgender women played a crucial role in the uprising, and figures like Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson should be at the center of any commemoration of the event.

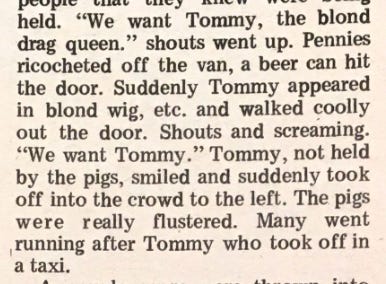

The narratives around the riot’s chronology are a bit muddled, but in every version self-identified “drag queens” played a key role, whether it was one of their arrests being the trigger that set off the resistance of the crowd around the Stonewall Inn or one of their numbers throwing the first brick. Here’s a contemporary account of a drag queen identified only as “Tommy” being thrown into a paddy wagon and then, thanks to the protests, being released.

Their story is tightly intertwined with the other gays and lesbians in the crowd on Christopher Street, and that’s entirely the point.

As we’ll hear a lot today (I hope!), the Stonewall riots were crucial in the public rise of gay and lesbian liberation.

But there was a longer history there, too. Just as there was a longer history behind the actions of Rosa Parks and the start of a commonly recognized civil rights movement, there was also a longer history behind the Stonewall riots and the start of a publicly identified movement for gay and lesbian liberation.

First of all, it's important to remember that the repression against homosexuals that the Stonewall riots were resisting was actually a fairly recent development. Indeed, as the historian George Chauncey has shown in his brilliant study of New York City, there were several thriving communities of homosexuals in New York from the 1890s through the 1940s. The common understanding that, before Stonewall, all gay men kept their sexual orientation a secret – that they were "in the closet" — is just wrong.

As Chauncey and others have shown, homosexuals created an open and accessible gay world in New York and elsewhere, but the impact stretched well beyond those enclaves. My terrific colleague Margot Canaday authored a fantastic account of the ways in which various aspects of the federal government — the military, immigration officials, New Deal welfare agencies — shaped our understanding of homosexuality and were shaped by it in return.

But during World War II, public attitudes began to change and homosexual activity was driven underground. Army psychiatrists introduced a new concept of homosexuality as a personality type that was unfit for military service and combat – as, in fact, someone who was mentally ill. (Check out Allan Berubé’s classic book on gays in WWII if you haven’t already.)

As a result, homosexuals were committed to hospital psychiatric wards and eventually discharged from the military as “psychopathic undesirables.” From 1941 to 1945, more than 4,000 sailors and 5,000 soldiers were thus discharged. An unintended and ironic consequence of the military’s policies was the establishment and growth of a thriving homosexual community in one of the Navy’s major port cities – San Francisco.

When the war was over, the wartime approach to homosexuality spread into other aspects of government life. In June 1950, the Senate authorized a formal inquiry into the employment of "homosexuals and other moral perverts" in government.

The ensuing panic — what historian David K. Johnson has called “the lavender scare” — prompted an Eisenhower executive order barring gays and lesbians from federal employment, and trickled down to the local level in waves of police raids and public humiliation that did, in fact, drive a new generation of gays and lesbians “into the closet.” (FYI: David’s book is the basis for a great documentary of the same name.)

So, yes, let’s be sure to remember that every part of the LGBTQ coalition was deeply involved in the Stonewall Uprising. But let’s not forget that there was much more to the history of LGBTQ Americans, out and in the open, for a long while before that.

My father’s best friendship — forged at Queen Anne’s Battery in Plymouth, England during its run up to D-Day — with my adored Uncle Murray happily colored my childhood, my teen years, and long afterwards. Many years after 1944, Uncle Murray died from HIV wrought diseases. My reaction to the current conservative push back as to people who don’t conform is to

stand straight and tall against such bunk.