Today marks the 75th anniversary of President Harry Truman’s order banning segregation and discrimination in the American military.

Though he had grown up, in many ways, as a southerner and even used racial slurs, Truman was deeply shaken by the wave of violence and discrimination that greeted many black veterans when they returned home from the war.

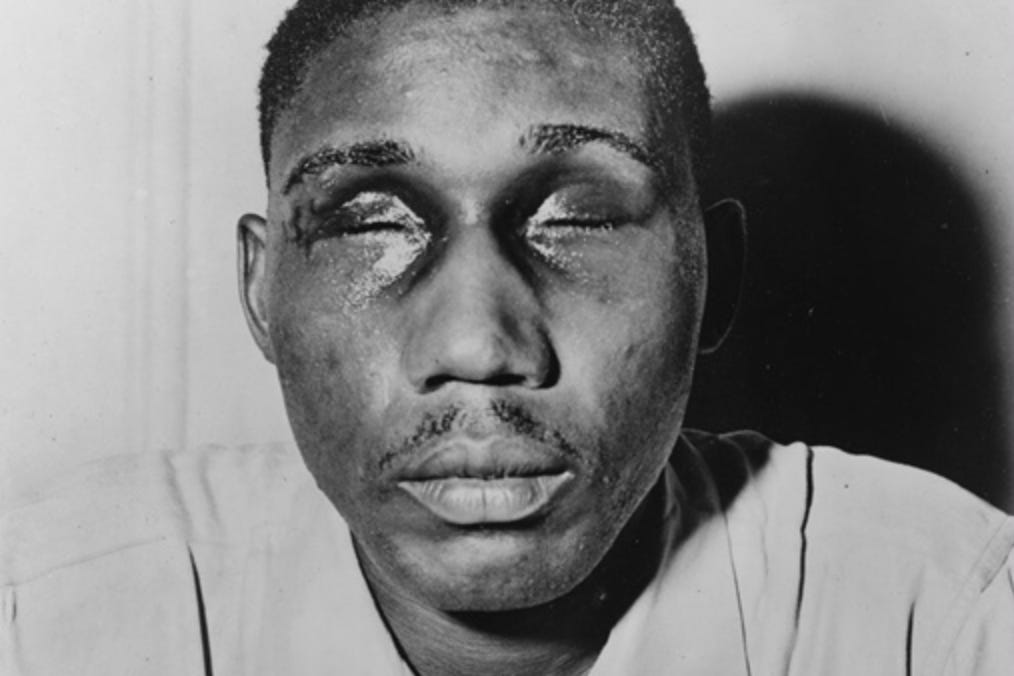

One story in particular sickened him – the story of Sergeant Isaac Woodard.

Sgt. Woodard had served in the Pacific Theater during World War II. In February 1946, he received an honorable discharge at Camp Gordon in Augusta, Georgia, and then boarded a Greyhound bus home to North Carolina. When the bus stopped in Batesburg, South Carolina, the local sheriff and his men dragged the black veteran off, took him into an alley and beat him with their nightsticks. They then arrested Woodard for disorderly conduct. That night, while Woodard was a prisoner in his jail, the sheriff repeatedly gouged his billy club into his eyes until he was permanently blinded. Suffering amnesia from the beatings, Woodard had no idea what had happened or even who he was. Nevertheless, he was hauled before a judge and convicted of disorderly conduct. It was three weeks before his family could find him.

Incidents like these outraged President Truman, and led him to announce the creation of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights in late 1946.

To the delight of African American leaders, the committee was staffed with a set of distinguished liberals who seemed intent on exposing the worst incidents of racism and discrimination. In 1947, the committee released its report, titled To Secure These Rights.

The report called for increased federal involvement in the realm of civil rights and made a number of specific recommendations — ending racial segregation, making lynching a federal crime, ending the poll tax and adding new protections to secure voting rights, ending racial discrimination in interstate travel, and more.

Although the commission’s recommendations were radical for the era, Truman stunned the nation by embracing them completely. He endorsed the report in full in his State of the Union address and urged Congress to act. At the time, a conservative coalition of Republicans and Southern Democrats controlled both chambers, and all these measures were quietly shelved.

With Congress unwilling to act, Truman proceeded on his own. For instance, he ordered his Department of Justice to do whatever it could to protect the rights of African Americans and had his administration file amicus briefs in support of civil rights organizations with cases before the Supreme Court. By 1952, the Truman administration was openly siding with the NAACP in its campaign to end segregation in secondary and elementary schools.

More immediately, on this date in 1948, Truman issued Executive Order 9981, calling for the end of all racial discrimination and segregation in the U.S. military.

The timing was important here.

Just two weeks before, the Democratic National Convention had formally backed Truman’s embrace for civil rights. This was a huge change for the Democratic Party, which had long been the champion of slavery, segregation and white supremacy. But Truman had set down a marker, and other liberal Democrats picked it up.

In the most important speech of the convention, Minneapolis Mayor Hubert H. Humphrey called on the party “to get out of the shadow of states' rights and to walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights.” (Seriously, give it a listen.)

Riding the positive reaction for the speech, liberal Democrats managed to push through a strong civil rights plank. And in furious reaction, the segregationist delegations from Mississippi and Alabama stormed out in protest, prompting the third-party Dixiecrat rebellion.

Truman’s executive order, issued not even two weeks after Humphrey’s speech, was meant as a sign — a sign that if the “do-nothing 80th Congress” wouldn’t enact his civil rights proposals, he would do so himself, and a sign that his commitment to civil rights went beyond words to actual deeds.

Now, the order would prove difficult to implement given that there was no timetable. As a result, some military divisions were still segregated during the Korean War. But the decisive change had been made, and the military soon became the model for successful integrated life in postwar America.

But it’s important to remember that the path to that point was not remotely clear when Truman issued the order.

Truman’s executive order proved to be deeply unpopular with the American people. A month before he issued it, the Gallup Poll asked "Would you favor or oppose having Negro and white troops throughout the U.S. armed services live and work together, or should they be separated as they are now?" Respondents favored segregation to desegregation by a whopping margin of 63 percent to 26 percent. Not even white veterans, who had just defeated the Nazi machine and witnessed the evils of weaponized white supremacy, welcomed the idea.

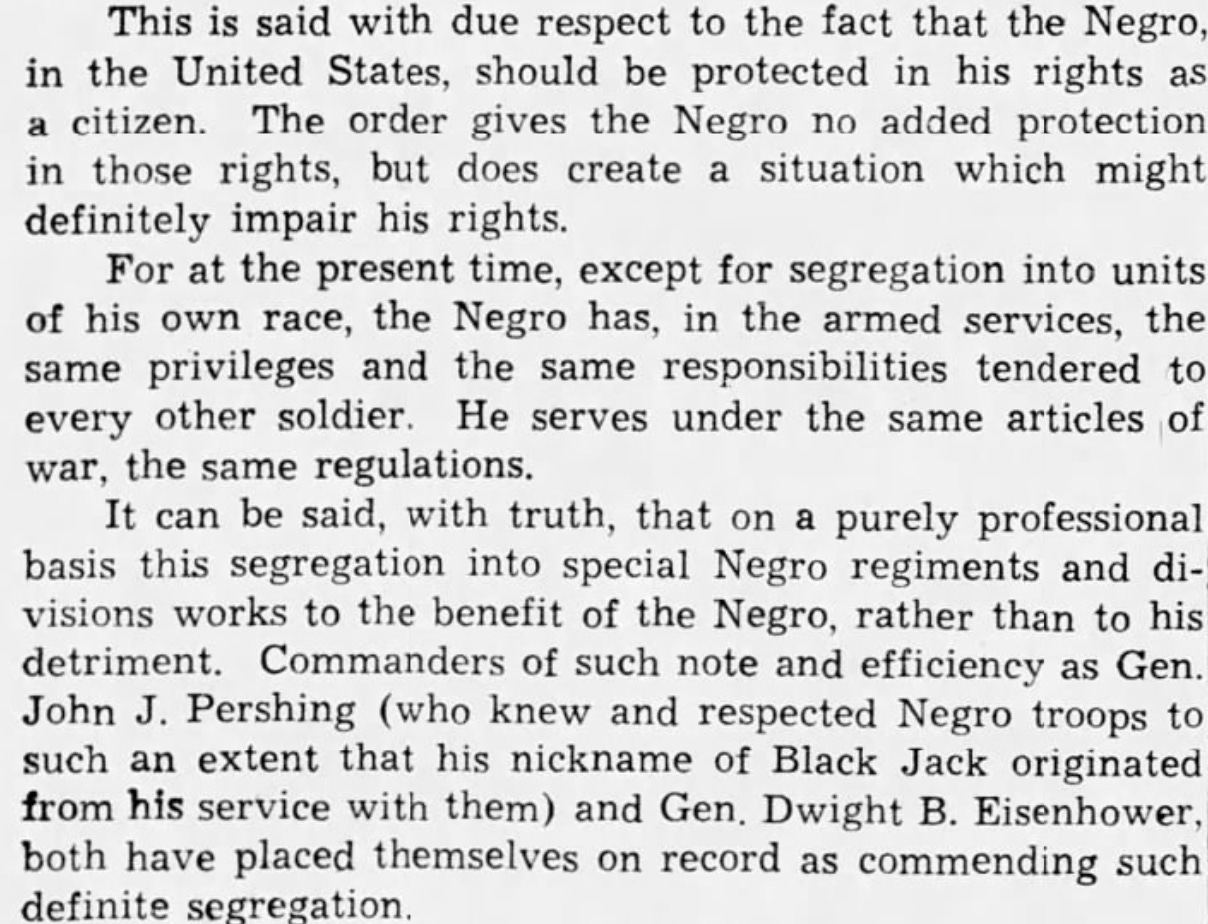

Some argued, as the Arizona Daily Star did, that black soldiers were absolutely thriving in the segregated military and forced integration would only make their lives worse:

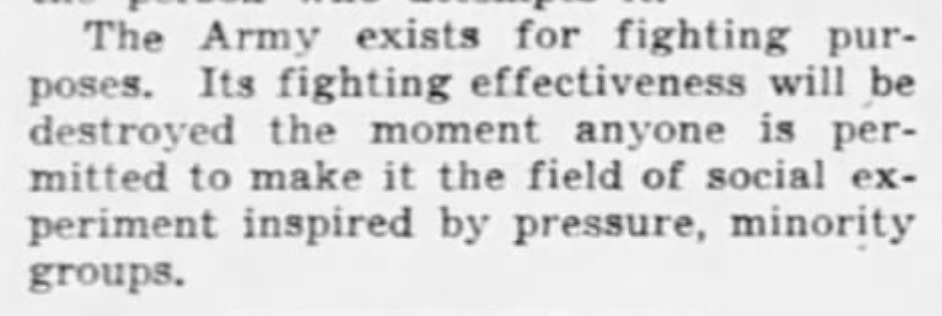

The most common complaint was that breaking down discrimination in the ranks was nothing but a political stunt and a “social experiment” that would weaken the effectiveness of the U.S. military.

Here’s an example from the Memphis Commercial Appeal:

If that sounds familiar, it’s because the exact same claim — that the military isn’t suited for “social experiments” — was dusted off and trotted out again to object to combat roles for women.

And then trotted out again to object to the open service of gays and lesbians.

And now transgender service members.

And so it goes.

Of course, the dire warnings that integration could only lead to disastrous results, both for the military as a whole and African Americans in particular, showed that those warnings were completely wrong. The U.S. military became one of the most successful sites of integration in American society.

These days, we’re often hearing complaints from the right that the military has gone “woke” for one reason or another, and that as a result of said wokeness, our military won’t be able to compete with more “traditional” militaries abroad. (See professional podcaster and occasional senator Ted Cruz’s complaint about a “woke, emasculated” military.)

When you hear such complaints, just remember that Truman’s actions 75 years ago were condemned in the same tones. Desegregating the military was deeply unpopular and doomed to failure … until it was actually tried.

If it was a “social experiment,” it’s one that succeeded wildly.

Thanks for doing this entire series. I am enjoying it and understanding these events in a context that I missed during HS history.

Thanks Professor for this important series of articles! It’s absolutely stunning to me that the same rationale is being used today in political discourse.