President Joe Biden made history today by joining the United Auto Workers on a picket line in Michigan.

“Wall Street didn’t build this country, the middle class built this country, and unions built the middle class,” he reflected. “That’s a fact, so let’s keep going. You deserve what you’ve earned, and you’ve earned a hell of a lot more than you’re getting paid.”

In the grand sweep of presidential history, this moment is, to borrow a Bidenism, “a big fucking deal.”

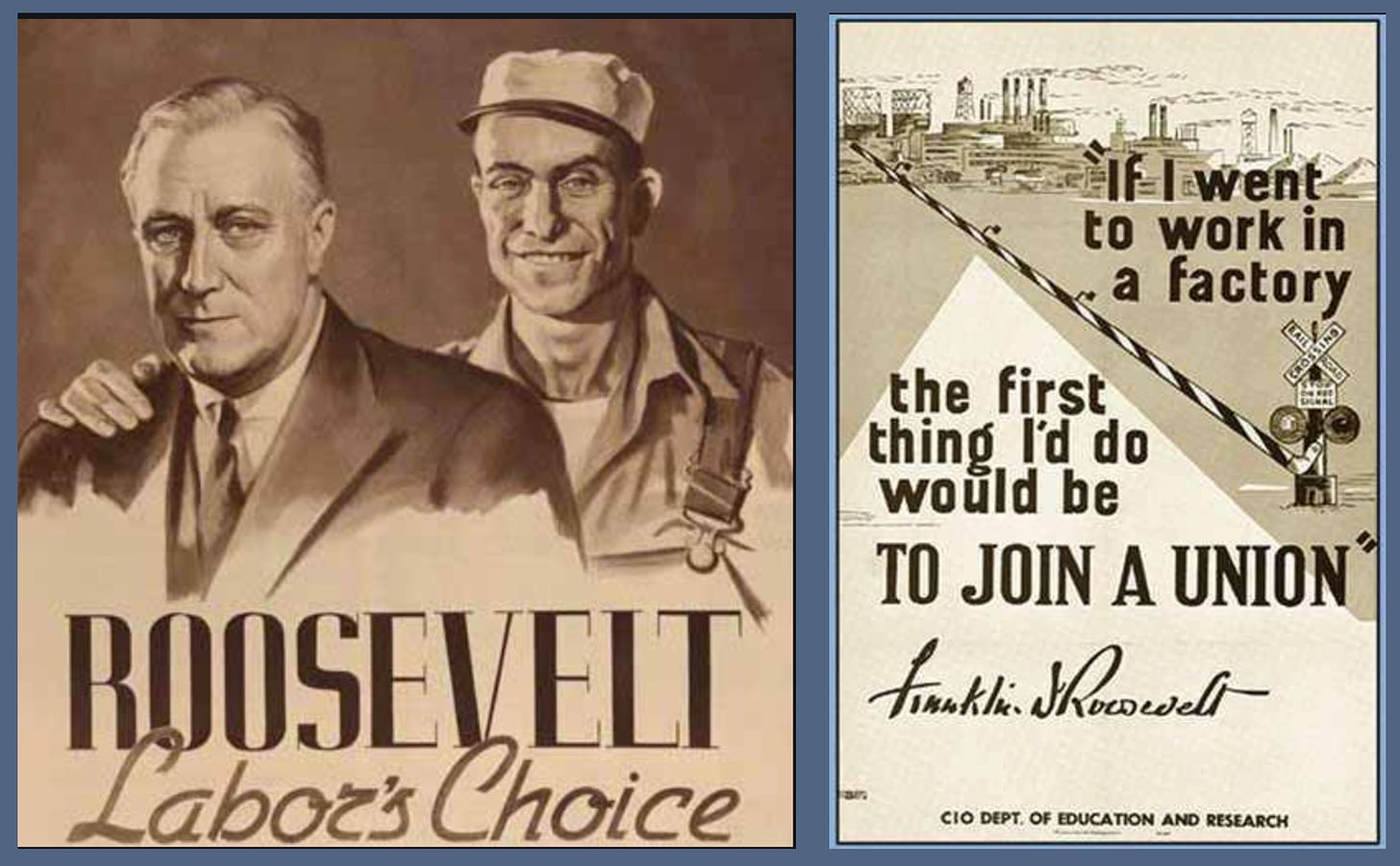

Not many presidents have supported unions in the past, and when they did, it was always a bit half-hearted. Yes, even FDR.

In the eyes of both his supporters and his enemies, Franklin D. Roosevelt was seen as a strong advocate of the working man. A millhand from North Carolina put it simply: "Mr. Roosevelt," he said, "is the only man we ever had in the White House who would understand that my boss is a son of a bitch."

Unions certainly tried to cultivate this image. When the legendary labor leader John L. Lewis went about organizing the coal miners in 1933, he used FDR in his sales pitch. "The President wants you to join a union," he told them. Likewise, his organizers were told to end all their speeches by holding up their crossed fingers and saying that "John L. Lewis and President Roosevelt, why they're just like that!"

In truth, however, FDR was a lackluster champion of the organized labor unions. As the historian David Kennedy put it, if FDR really were the "worker's patron," "it was also true that his fundamental attitude towards labor was somewhat patronizing." Roosevelt thought that working men simply needed protective measures of the government – his pension and unemployment protections, along with wage and hour legislation – instead of the right to bargain collectively and thereby protect themselves.

When the labor organizing of the late 1930s reached its crisis point — the infamous “Memorial Day Massacre” at the Republic Steel plant outside Chicago, where police gunned down striking steelworkers, killing ten and wounding many more — FDR’s half-hearted support became clear.

On one hand, FDR believed the unions had the right to organize and even agitate for better working conditions. When company owners begged him to use federal force to drive out workers engaged in sit-down strikes, he refused and told them to be patient. The strikes were, he noted, a “damned unpopular” tactic and in time the unions would realize that too. “It will take some time, perhaps two years,” he reasoned, “but that is a short time in the life of a nation.”

On the other hand, as that same quote suggests, FDR understood that the strikers themselves were becoming “damned unpopular” with the general public. While he did not support the use of deadly force against the strikers, he did not believe the strikers themselves were wholly blameless.

In the end, he decided to wash his hands and cast blame on the unions and the corporations alike. In a press conference in June 1937, he quoted Romeo and Juliet: "A plague on both your houses."

This sort of balancing act was followed by FDR’s Democratic successors. (Truman, for instance, had a long record of supporting unions and being supported by them, but even his presidency featured major showdowns with the coal and railroad unions.)

There’s certainly still more Biden can do to support labor in this country, but today’s appearance is an historic show of sympathy — and perhaps a sign of more to come.

As I watched this historic moment, I was imagining Barack Obama whispering to Biden that it was indeed, a BFD. Proud of the President for showing up. Proud of the union for standing up.

I’m enjoying this labor movement renaissance.