In recent months, the breathtaking radicalism and brazen corruption of the current Supreme Court has reignited the longstanding debate over reforming the Court by expanding the number of Justices.

As often happens, these discussions about a potential change in our government are shaped significantly by our understanding — or misunderstanding — of the history of those institutions and past efforts to reform them. Two points, in particular, stand out.

The first misunderstanding, that the current shape of the Supreme Court was designed by the founders and never tinkered with before, has been thoroughly debunked by the great historian Holly Brewer in this New Republic piece. As she notes there, the Court’s size was repeatedly changed during the nineteenth century, with several changes made explicitly to address concerns about the Court’s political bent.

The second misunderstanding revolves around the so-called “Court-Packing Crisis of 1937” initiated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in his long-running fight with the conservative Court of his era. The plan failed and, nearly a century later, Democrats are still haunted by that failure, afraid to try it again because they’re sure it’s doomed.

But that’s entirely wrong.

Let me back up here, and offer some context. (Many of the quotes below come from Bill Leuchtenburg’s outstanding essay collection The Supreme Court Reborn, so check that out if this piques your interest.)

In the mid-1930s, the Supreme Court was divided into clear ideological blocs. There were four archconservative justices — “the Four Horsemen” — who invariably ruled against the New Deal legislation that came before them, usually joined by a pair of swing justices. The result was a string of 5-4 or 6-3 decisions that struck down liberal legislation.

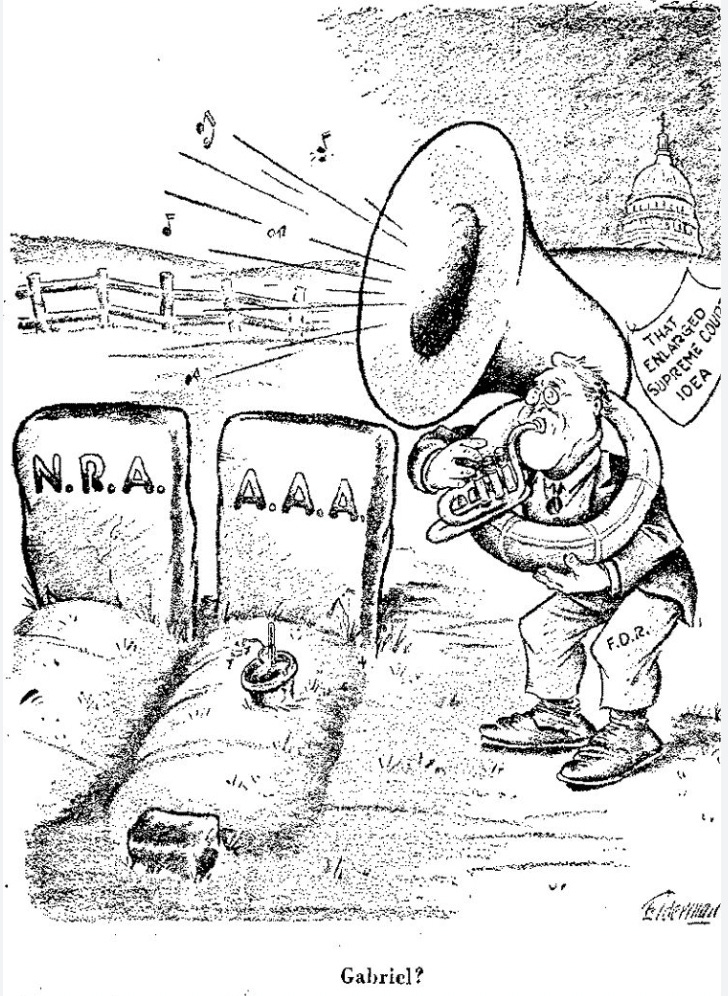

They struck down the National Industrial Relations Act, the New Deal’s original plan to bring back business and industry, with a 9-0 decision in 1935. Then they struck down the Agricultural Adjustment Act, the New Deal’s original plan to revive a crippled farming sector, with a 6-3 decision in 1936. Emboldened, a 5-4 majority then laid waste to other New Deal reforms throughout the rest of the year.

There was, to be sure, considerable outrage over the Court’s decisions. Newspapers blared out banner headlines when the NIRA was struck down, calling the day “BLACK MONDAY.” Furious farmers in Iowa responded to the AAA decision by erecting a gallows and hanging effigies of the six justices who ruled against it. Even Herbert Hoover and the Republican Party thought some of the decisions went too far.

After his landslide re-election in 1936, FDR decided to attack his enemies on the Court head-on.

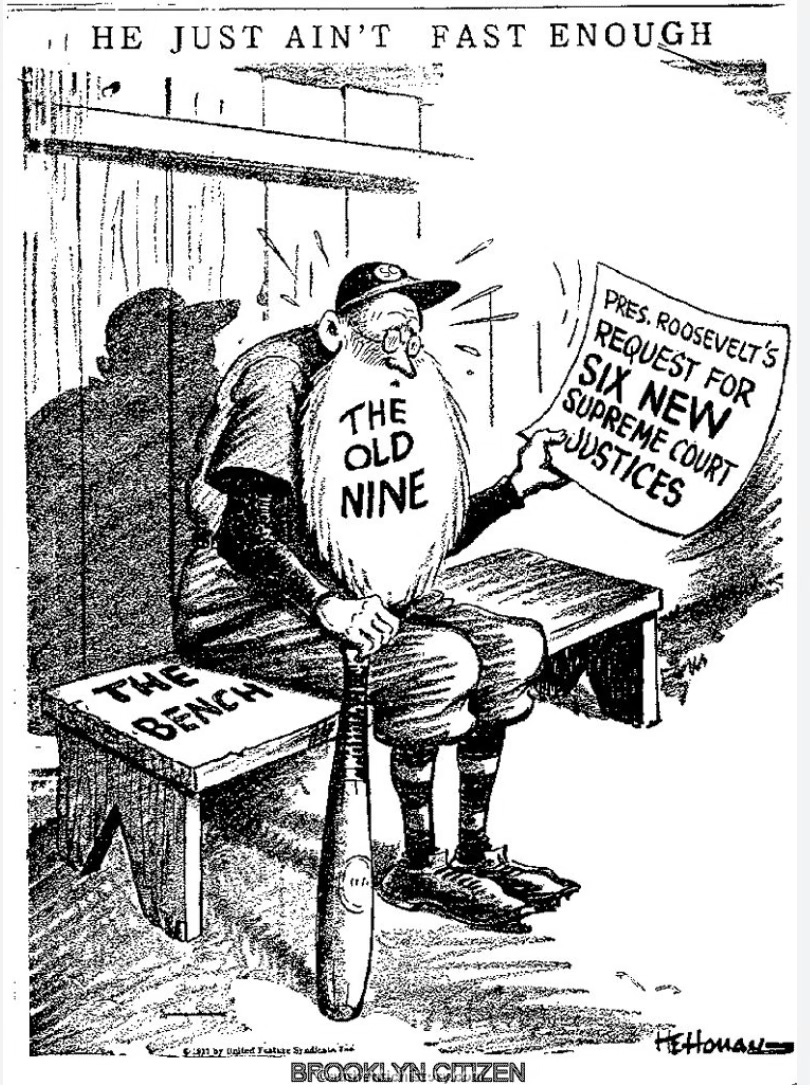

On February 5, 1937, the president sent Congress his plan for reorganizing the judiciary. Disingenuously, Roosevelt introduced the proposal by claiming that a shortcoming in staffing had led to overcrowded federal court dockets. Specifically, he mentioned the "capacity of the judges themselves," noting that the average age of the Justices was 71.

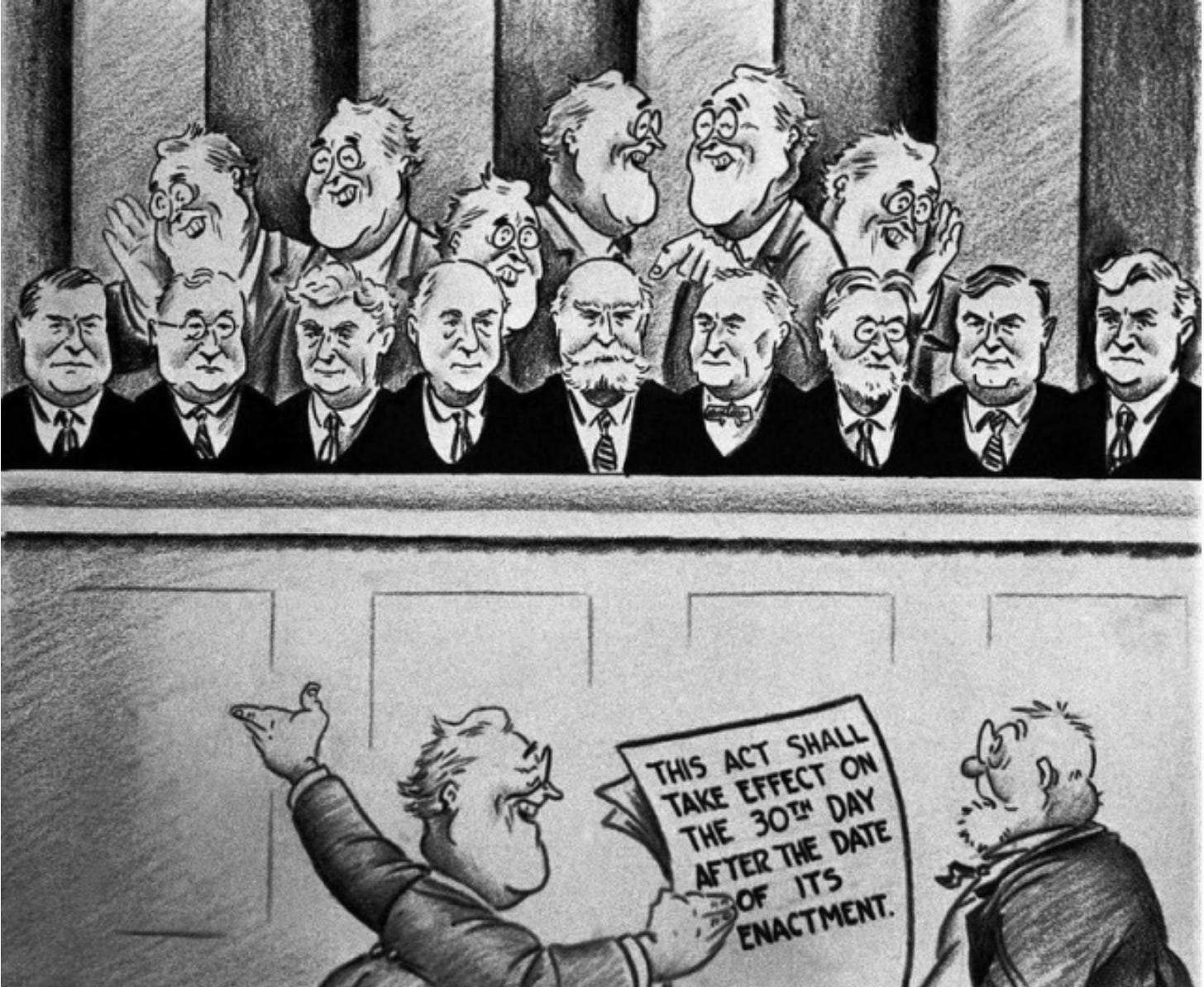

In order to "vitalize the courts," Roosevelt proposed a complicated formula for expanding them. Specifically, the bill proposed that when a federal judge who had served at least ten years on the bench waited more than six months after his seventieth birthday to resign or retire, the President could add a new judge to sit beside him on the bench. In concrete terms, this would have empowered FDR to appoint as many as six new Justices to the Supreme Court and forty-four new judges to the lower federal courts.

FDR’s critics tore through the plan. The old-age excuse seemed incredibly weak, they noted, as the oldest member of the Court was 80-year-old Louis Brandeis, who was not only quite active but also a strong ally of the administration. And in any case, the White House soon learned that a bunch of septuagenarian senators were not exactly amenable to the argument that people over 70 were too old to function properly.

Other critics cried out that, by trying to reform the Supreme Court, FDR was tampering with a venerable institution.

Some of FDR's supporters mocked the idea that the Court should be impervious to all change. The number of Justices had gone up and down in the past, they pointed out, but people now insisted that tampering with the Court was a sin. "To listen to the clamor," noted Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, "one would think that God himself had decreed that if and when there should be a Supreme Court of the United States, the number Nine was to be sacred. All that is left to do now is to declare that the Supreme Court was immaculately conceived, that it is infallible, that it is the spiritual descendant of Moses, and that the number Nine is three times three, and three stands for the [Holy] Trinity."

In spite of Ickes' sarcasm, many people thought of the Supreme Court in precisely those terms. "As a boy, I was taught to honor and revere the Supreme Court of the United States above all things," wrote a New Orleans man. "We were taught to think of it," a Charleston publisher wrote, "with reverence, as like the Church, where men selected for their exceptional qualifications presided as Bishops should." Indeed, in terms strikingly similar to Ickes' mockery, a Catholic layman seriously compared the Court to the Pope: "To all intents and purposes, our Supreme Court is infallible. It can not err."

The biggest blow to what critics now called “the Court-Packing Plan” came from the Supreme Court itself. As the Senate debated the plan, the Court issued a new set of 5-4 rulings that narrowly upheld key New Deal measures like Social Security and the Wagner Act. One of the “Four Horsemen” then announced his intention to retire, which meant FDR would get to appoint his first justice to the Court and thereby expand the new 5-4 majority into a safer 6-3 one.

It seemed like there was no longer any reason to press on with the reform plan. As Senator Jimmy Byrnes of South Carolina put it, "Why would you keep running for a train after you've caught it?"

But Roosevelt pressed on. His fight on the Senate floor was led by Majority Leader Joe Robinson of Arkansas, who had not coincidentally been promised the first open seat on the Court. The fight for the plan continued through the summer, tying up Congress and chipping away at FDR's public prestige. A sudden turn of events ended the fight. On July 14, 1937, Senator Robinson — who had been pushing the bill for long hours in the summer heat and humidity — suddenly died from a heart attack. And with his death, the Court-Packing plan died too.

For many politicians and pundits today, FDR’s Court-packing controversy stands as a cautionary tale that the Supreme Court must remain off limits. But if we study the tale closely, we can see that’s a serious misreading.

First of all, the popular perceptions of the Supreme Court have significantly changed.

While Americans held the High Court in high esteem a century ago and a majority therefore opposed the “Court-packing” plan, those are no longer the case. The Gallup Poll shows that the Court’s disapproval rating has reached 58%, which is now the highest level of dissatisfaction it’s ever seen in their tracking, nearly twice what it was a quarter century ago. And a recent poll shows why: 7 out of 10 Americans believe the justices are not impartial and are driven by their own personal political ideology.

Second, the radicalism of the current Supreme Court far surpasses the previous one.

FDR’s complaint with the Court of his era was that they refused to break with the limited government precedents laid down by earlier conservative Courts and therefore struck down the New Deal’s innovations as violations of those precedents. They were, in effect, using old norms to strike down new laws on which the ink had barely dried.

But the current Court is doing the opposite, reversing longstanding precedents that were established by previous Courts, ones that have stood the test of time for 40 or 50 years, including a specific one almost all of them directly swore under oath to protect. While critics of FDR’s plan painted him as the one recklessly overturning the established order and the Court as its besieged defenders, the roles have reversed now. The Roberts Court has been gleefully destroying longstanding norms, not solemnly defending them.

(Another way to think of this is that the Roberts Court started out doing the same sort of things as the Court in FDR’s era, striking down or partially invalidating brand new liberal laws like the Affordable Care Act, but the conservative majority has moved far, far beyond that point and is engaged in a reactionary campaign that dwarfs anything the Four Horsemen did.)

So, the Supreme Court is no longer as sacrosanct as it once was and the Supreme Court cannot portray itself as a victim here, as its conservative bloc has clearly been the aggressor and the violator of established norms.

Third and perhaps most important, we need to remember that FDR’s Court-packing plan didn’t really fail!

Sure, the plan itself died along with Joe Robinson in the Senate, but in the larger sense, FDR got the Court he wanted. Confronted with the challenge from a popular president, the swing justices on the Supreme Court moved away from the conservative bloc. Moreover, FDR got a chance to remake the Court with new appointments.

Within two and a half years, he was able to name five of his own appointees to the Supreme Court: Hugo Black, Stanley Reed, Felix Frankfurter, William O. Douglas, and Frank Murphy. This new Court – the "Roosevelt court" as it was called – had a much broader sense of what the federal government could do to intervene in the national economy than the Court had in the earlier years of the New Deal.

In many ways, that Court had been the last holdout of the old understanding of the relationship between government and business, one in which business was given a great deal of lee-way. The new Court, and the ones that followed it, were much more willing to subject free enterprise to government regulation and oversight. As one observer noted, “The businessman, who had for so long been the Court’s darling, was shorn of his constitutional fleece and now had to face the will of the people, protected by nothing except his own ample resources.”

At the same time, the new Court moved to safeguard the civil liberties of various racial and political minorities. As late as 1935, issues of civil liberties and civil rights were the focus of just 2 out of the 160 cases in which the Court delivered written opinions. Fifty years later, cases focused on civil liberties and civil rights would represent over half of the court’s docket.

For these reasons, legal historians focus not on the “Court-packing” debacle, but what they rightly characterize as “the Constitutional Revolution of 1937” that it ushered in.

In short, FDR might have lost the specific Court-packing battle, but he ultimately won the war over the Supreme Court.

Were there electoral consequences? Perhaps. Democrats took a beating in the 1938 midterms, but I suspect most political historians would assert that the middle-class resentment over the sit-down strikes by organized labor and the general blowback from the ongoing “Roosevelt Recession” of 1937-1938 were more important factors than the long-abandoned Court-packing plan.

For all these reasons, I’d suggest that today’s Democrats are simply drawing the wrong lessons from the “Court-packing controversy.”

The Supreme Court isn’t remotely the same institution it was then, both in the public perception of it and the actual conduct of its conservative bloc. Moreover, Court-packing wasn’t the catastrophe many believe it to be today. There were real benefits to FDR’s challenging the conservative bloc then and there would be even greater ones today.

Instead of listening to those who misunderstand the history of “Court-packing,” Democrats should adopt the framing used by Senator Robert LaFollette, Jr. to back FDR’s plan.

A Progressive Republican from Wisconsin, LaFollette argued passionately that the president wasn’t trying to “pack” the Court; rather, he said, FDR was trying to “unpack” the pro-business bloc that had taken it over in the preceding decades.

There is a lot of talk of the President “packing” the Court. Let’s not be misled by a red herring. The Court has been “packed” for years – “packed” in the interests of Economic Royalists, “packed” for the benefit of the Liberty Leaguers, “packed” in the cause of reaction and laissezfaire. Let’s be frank about this matter. The vested interests have for years prevailed in the selection of judges. Under our form of government the will of the majority should prevail. If the majority of the people want progress, they shall have it. [The 1936 election] made it clear and unmistakable where the vast majority of the people stand. They want to be free from the shackles of vested interests. They have rejected the Economic Royalists. In the words of Lincoln, they want a government of the people, by the people, and for the people. They cannot have it if the Supreme Court places itself above the Constitution and arrogates to itself legislative functions. One clear way in which they can have their will of last November expressed is to have the Congress “unpack” a Court which has long been “packed” by the forces of reaction.

Of course, this argument fell short at the time, because its basic cynicism ran headlong into the stubborn idealism that all too many Americans still had about the institutions of government.

But thanks to the ethical scandals and political gamesmanship that have come to define the current Supreme Court, the argument that the Court has been “‘packed’ by the forces of reaction” seems quite obvious. As a result, the argument that it now needs to be “unpacked” would carry much more weight.

Unpack the Court. It’s long overdue.

Interesting bit of history. Few talk about the Sumners-McCarran Act of 1937. It enabled Supreme Court justices to get a pension. Van Devanter retired right after it took effect. The irony was that McCarran strongly opposed the court-packing plan, and earned FDR's ire for it, but he helped him get rid of some of the justices!

Excellent summary. Thank you. There is so much work to be done educating the public not only on how horrific a turn the Court has taken but that they can actually do something about it. I gently cautioned a democratic influencer on Instagram to not use the terms "pack the court" for what we need to do to unscrew what Roberts has screwed up. The other side has used language masterfully for too long to beat us with a stick (tough on crime, all lives matter, pro-life and anti-woke). I like your use of UNpack the court. It sets the narrative on what they have already done.