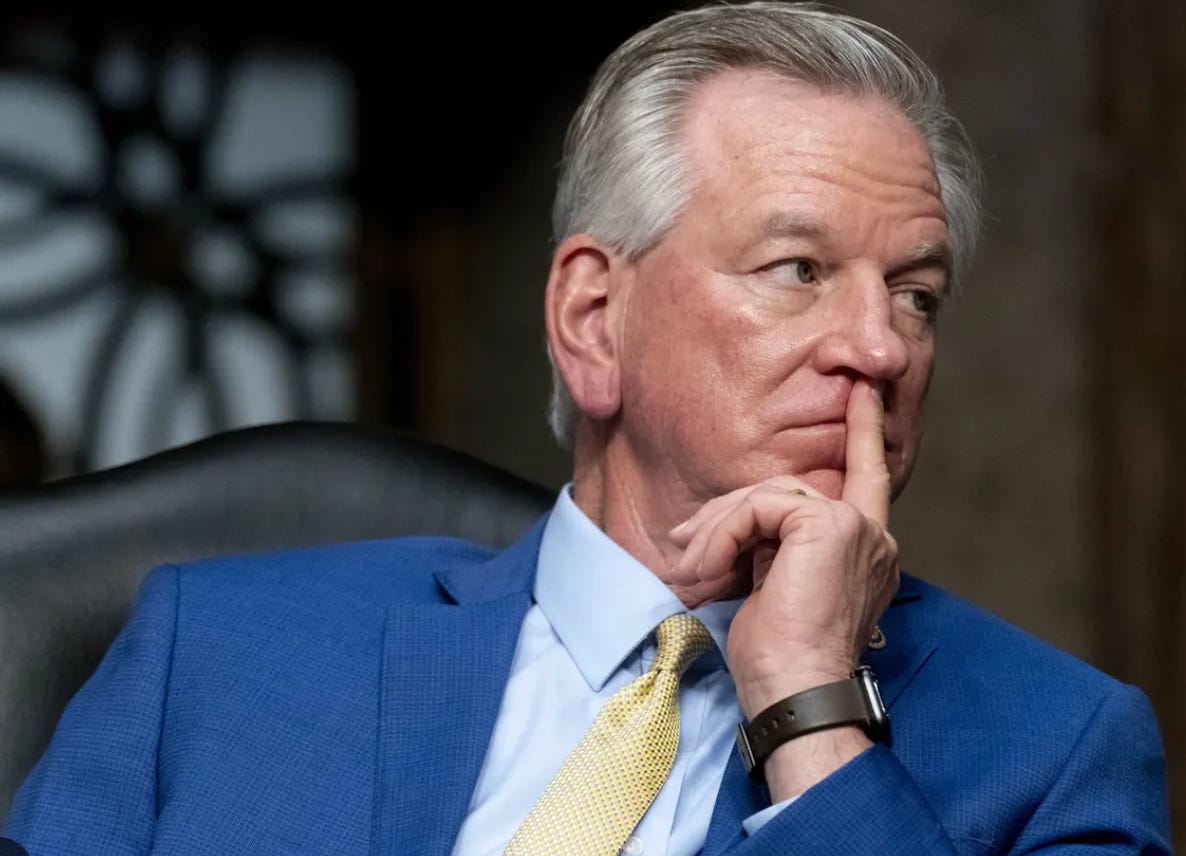

Last night on CNN, Sen. Tommy Tuberville once again refused to denounce white nationalism, insisting that white nationalists are not, in fact, racist and that such a characterization is merely “some people’s opinion.”

This is a line that Republicans in the Trump era have made themselves walk. They agree, as Tuberville did in that interview, that “racism” was bad but then contort themselves into comical knots insisting that wide swaths of avowed racists are not, in fact, racist.

It’s a dangerous line that Republicans have walked before.

During the 1964 presidential campaign, the party followed its new Southern Strategy to win over white segregationists across the South. The party’s ticket was, as I’ve argued elsewhere, “the Southern Strategy personified,” with presidential nominee Senator Barry Goldwater having voted against the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and vice presidential nominee Representative William Miller having implemented the strategy on the ground as chairman of the Republican National Committee.

Their plan worked, but all too well.

Republicans won the support of rank-and-file segregationists across the South, but also secured high-profile endorsements from leaders of the Ku Klux Klan. Robert Shelton, Imperial Wizard of the United Klans of America, announced he supported Goldwater not as an individual candidate, but instead "for the principles that the Republican Party has adopted in its program.”

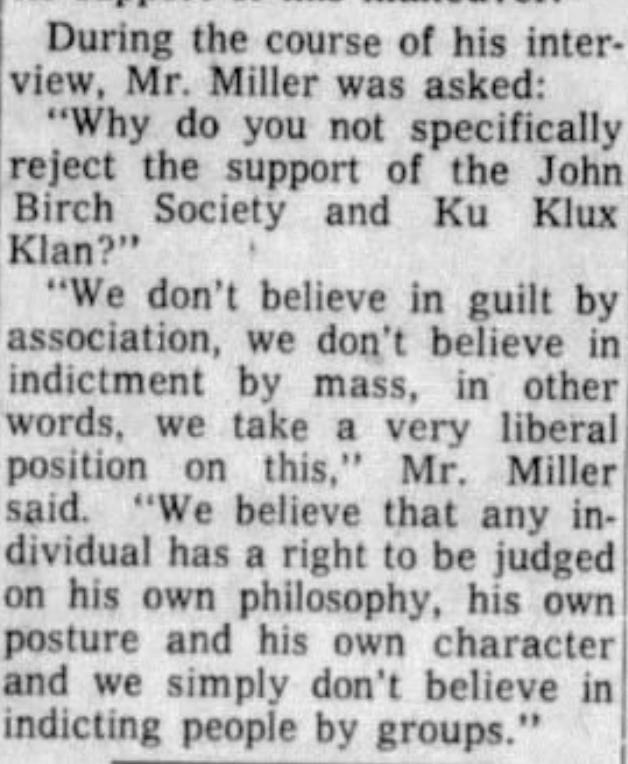

When national reporters asked the Republicans if they welcomed the endorsement of Klan leaders in the South, party leaders repeatedly refused to distance themselves from the white supremacist organization. In early August, vice presidential nominee William Miller rejected what he called “guilt by association”

Refusing to condemn white supremacists, Miller announced that “Sen. Goldwater and I will accept the support of any American citizen who believes in us, our attitude and our posture.”

Republican National Committee Chairman Dean Burch echoed his stance with a dismissive comment: “We’re not in the business of discouraging voters.”

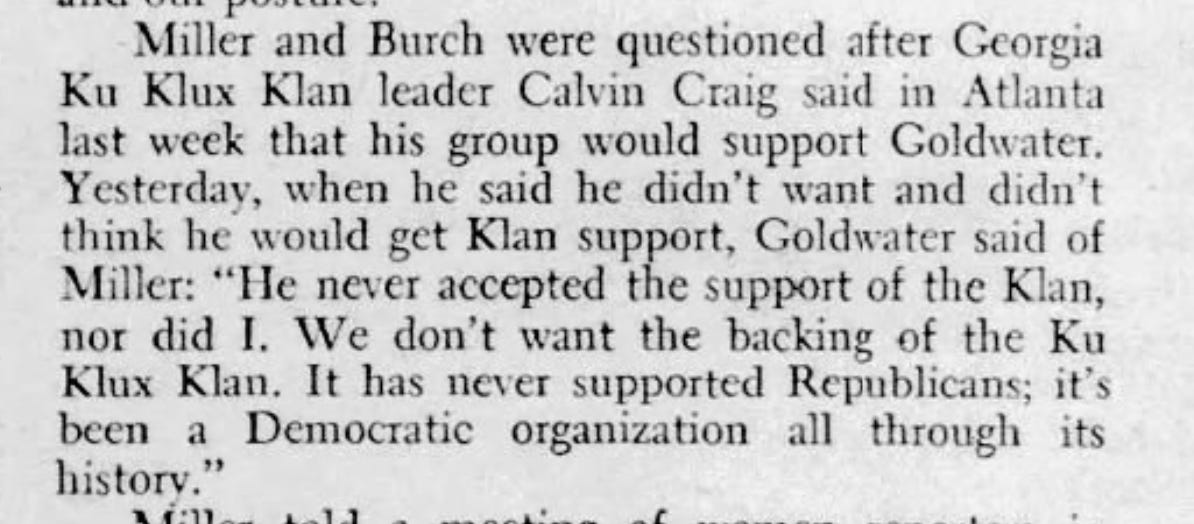

Party elders, however, realized that such a stance would be an electoral disaster. After a hasty meeting with former president Dwight Eisenhower, Goldwater emerged to issue a clear denunciation of the Ku Klux Klan and to deny he ever wanted — or actually had — their support.

In a dodge that’s all too familiar to us today, Goldwater insisted that the Klan couldn’t possibly support the Republican ticket because “[i]t has never supported Republicans; it’s been a Democratic organization all through its history.”

(That last claim, we should note, is absolutely not true. While the “first Klan” of the Reconstruction era was absolutely aligned with southern Democrats, the “second Klan” of the 1920s had divided its support between the parties. In states like Indiana, the Klan was deeply intertwined with Republican politics — with disastrous results.)

Despite misrepresenting the past, Goldwater understood the politics of his present moment required a clear denunciation of the Ku Klux Klan. Wooing “respectable” segregationists was one thing; getting cozy with the Klan was quite another.

Coach Tuberville, however, sees things differently in our present moment. As he sees it, white nationalists aren’t something to be condemned. It’s only “some people’s opinion” that they’re racist, after all.

History, in fact, rhymes. Tuberville's contortion is no surprise. He remains solidly on brand. The silence from others who look like him, in his generation, from the South -- for instance a certain ex-President -- is deafening.

Tuberville and his ilk often try to justify their positions by adding the word "Christian" to their views, which seems to them to make racism okay. By trying to "baptize" their racist views they are appealing to the knee-jerk responses of many Americans. The merger of nationalistic and Christian views is particularly odious--and dangerous.